"I had access to resources only after I was incarcerated": an interview with Adnan Khan, executive director of Re:Store Justice

Plus links that explain felony murder and major congratulations to Lina Khan!

Dear all,

Happy Juneteenth & Happy Father’s Day!

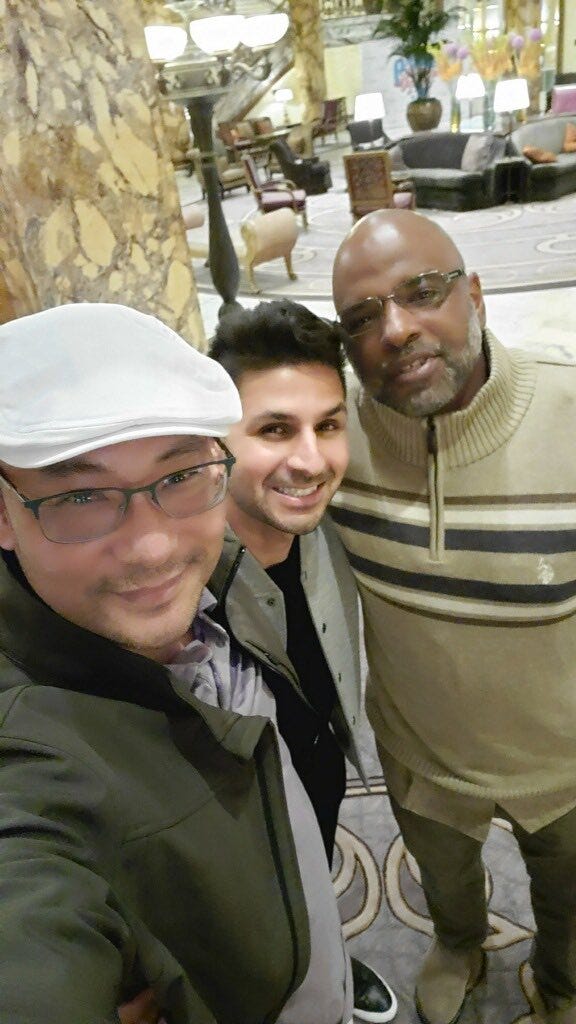

We were honored to speak to Adnan Khan, a formerly incarcerated person and advocate who spent sixteen years in prison in California. He is the executive director of Re:Store Justice, which he founded while there.

Muslim and Pakistani American, Adnan was arrested at eighteen on a felony murder conviction. In January 2019, the California legislature passed a bill scaling back prosecution of felony murder, a criminal law doctrine that allows defendants to be convicted of first-degree murder if a victim dies during the commission of a felony.

Adnan was the first to be released following the bill’s passage. Today, in addition to his advocacy at Re:Store Justice, he’s known for his brilliantly lucid tweets. (You may remember, from a previous newsletter, a particularly moving thread around Ramadan about how prison discourages kindness and charity to others.)

We first met Adnan when one of our students invited him to a virtual conference on prisons, punishment, and justice. We were moved by his graceful presence, eloquence, and sense of humor.

In Part 1 of this interview, he shares how abuse affected his ability to focus in school and how he managed to survive as a homeless teenager. He talks about working to heal his relationship with his mother and about studying the history of his parents’ native Pakistan while in prison, which helped him understand intergenerational trauma. He also explains that the rates of Asian and Pacific Islander incarceration have increased in California, situating them in the context of intergenerational trauma and American imperialism.

Albert: You were eighteen when you were arrested and incarcerated. Could you share a little bit about your life before that?

Adnan: My parents are immigrants from Pakistan. They came here in the early eighties and had three children. My two sisters and I are three years apart. And we were all born in May! So we’ve always been close.

My parents came together through an arranged marriage in Pakistan. They experienced a lot of trauma in their lives, including multiple wars and the partition in 1947. My mom is the eldest of eight children—four boys, four girls. I have a lot of aunts and uncles. But even when I lived with them, the household was filled with verbal and physical violence, rooted in their trauma from the war.

When I was eight, my parents divorced. My father was always an absent father, addicted to alcohol and gambling and in and out of my life. He wasn't smart with money; the little money we did have came from my mom, who was working consistently.

Before I go further, let me fast-forward real quick. After I had spent eight years in prison, I finally got to rekindle my relationship with my mom using an illegal cell phone. I wanted to heal some of the traumas from my childhood. I asked her, “Did you ever fall in love with Dad?” She paused and said, “No, I never had the time to fall in love with your dad. Your older sister was born and the alcohol, the odd jobs, the money, the arguments all started immediately.”

My mom remarried. I had an abusive stepfather. He would take food away from me or hide it. He threatened to kill me, and tried to poison me one time. He had my stepbrothers—they were in high school and I was in sixth grade—steal money or jewelry from my mom and put it in my jacket pocket; then he’d tell my mom, “Adnan is stealing. He's a bad kid, we should punish him.”

I went through that for almost a year until I rebelled. I just didn't want to take it any more. From then on, my safest places were with my friends. As a teen, I coped by drinking alcohol. As I got older, I began to cut school.

I went to different schools because I couldn't focus in the classroom. I had too much emotional baggage and trauma for my brain to process math or history or English or literature. And there was no safe place for me to express my grief or seek help. Instead, when I acted out, school would punish me. Detentions, expulsions, and suspensions were common.

By the time I was seventeen, I hadn’t seen my dad for three years. My mom divorced my stepfather and moved out of state to get married for the third time. A month later, I was kicked out of my house by my uncle, so I lived homeless for about a year. I slept in cars and parks, at friends’ houses, wherever I could. I remember a couple of nights on a tennis court.

I was homeless when I turned eighteen. With all these layers of trauma added to the conditions of being a homeless teenage high school dropout, I committed a crime and committed harm. I was charged with felony murder and sentenced to twenty-five to life.

Michelle: How did you keep going during that year? Was there anyone who could help?

AK: There wasn't anyone I could turn to besides friends who were my age or a few years older. It was very uncomfortable living in other people's homes, spending a night here and there, sneaking around. The friends I did turn to were the people who set up the crime I ended up going to prison for.

I did enroll myself in adult school but I didn't have enough money to continue. I couldn’t even pay for transportation to classes, so I had to drop out.

I lived in a car with a broken transmission. It was my mom’s old car, a 1991 Toyota Corolla. Somehow I got it into the guest parking lot of an apartment complex and slept there for almost six months. I was always worried it would be towed. Every night, I would walk up this tree-covered hill with this fear of the car not being there.

But when I went to the other side of town or somewhere else with a friend, I wouldn't be able to get back to the car. It was too far. I didn’t even have even a couple of dollars to get on the BART. I did enroll myself in adult school but I didn't have enough money to continue. I couldn’t even pay for transportation to classes, so I had to drop out.

I remember taking the bus to this area where I figured I could sign up for Section 8 housing. I went into this little office in the middle of nowhere. There were women with little children, babies crying. They handed me this clipboard, and I remember them giving me a funny look: What are you doing here?

When they told me it would take a year or two to get off the waiting list, I felt so deflated, so angry. I needed help now! I really needed a shelter. You know, people often say you can lift yourself up by your bootstraps. But how? When I’d interview for jobs and tell them I didn’t have a high school diploma, they’d say, “I’m sorry.”

The little things added up. I remember shamefully asking for coins and using that money to get detergent, then doing my laundry in that apartment complex. It was shameful too when I asked friends, “Hey, can I iron my clothes here?” I remember wearing two or three layers of clothes to a friend's house so I could use their iron. Toothpaste and toothbrushes were too expensive.

Maybe I could have tried harder, but nothing was accessible. That early experience grounds a lot of my advocacy. The police showed up, the prison showed up; I had access to resources only after I committed harm. And I'm not saying the state should have provided me with a parent, housing, or even a role model. But the housing and the food came when I was incarcerated. All of it was crappy, but all of a sudden I had access to resources. After I committed harm. After someone was hurt. All of that damage in the community could have been prevented.

Being homeless was shameful. Being uncared for, being kicked out of the home at seventeen, feeling like you don’t matter—there was a lot of pain there. A lot of grief. And that evolved into anger and self-hate, and wanting to medicate with weed and alcohol to the point where I impulsively agreed to steal a thousand dollars’ worth of weed. That’s why I ended up going to prison for a life sentence.

MK: I was very moved to hear you on the Ear Hustle podcast (listen here, transcript here), talking about being visited by your mom after thirteen years of being incarcerated. You shared what it was like to prepare—practicing the air hug in the cell before you saw her. I'm wondering, how is that process of healing now?

AK: We are in a completely different space compared to ten, fifteen years ago. The heavy resentment I once had—it's not completely gone, but it's almost eradicated.

Of course, there are still triggers. I try to ground myself in forgiving my mom for neglecting me, for believing my stepdad instead of me. I have come to understand her hurt and pain. It wasn’t until much later that I learned that my stepdad would sedate her; he’d tell her, “Hey, take this medication, it’ll make you feel better.” So once I forgive her, I have to keep reminding myself when those triggers come up.

Obviously, a lot of my mother’s guilt comes from her belief that my incarceration was directly her fault. On my end, I reject being treated like a kid; no matter how much I work on our relationship, I feel like saying to her, “Don't try to be a mom now.” It's something I continue to work through with her.

What I’ve learned is that we will always be angry. It's what you do with that anger, how you react with it, that counts. I've also learned that emotions are tiered, and anger is secondary. There's an underlying emotion: fear, shame, grief, or some other form of trauma comes first.

I’ve also realized that it’s okay to be mad. When I first got out, we didn’t talk about anything. She wouldn’t get mad at me, I wouldn't get mad at her. We had a surface relationship; we were avoiding the actual things happening in our lives. So I think the ability to get mad at each other strengthens the relationship.

All in all, my relationship with her today is great. She has a grandson, my baby boy. She's so happy and can't wait to meet him. So when we text, when we call each other, it's joyful. It's happiness.

Sometimes we do argue about my sister. I will team up with my sister because my mother’s so traditional, and she tries to force herself into my sister’s life. She wants my sister to get married—she's one of those. “Get married, you’re not married yet. Get married.” My sister confides in me; just a couple of weeks ago, she texted me a picture with the caption, “Mom just sent me a picture of this guy. She wants me to marry him.” And I started laughing. We were making fun of him for being bald. I sent back a GIF of an egg. [Laughter] And when I talked to my mom, she told me he was a police officer!

MK: You sound like such a good brother. Also, doesn't your mom read your tweets? I mean, a police officer? [Laughter.]

AK: My mom has no idea what I do. [We all laugh.] If I ask her, “Do you know what I do?” She’ll say, “Oh, you’re doing great work.” But that’s the extent of it.

MK: Maybe I’m projecting here, but I think part of what's so difficult is that sometimes we have to articulate to ourselves the political context of our parents’ traumatic histories. You had to piece together Pakistan and the partition, make sense of it yourself. American education doesn’t teach much outside of the U.S., much less about imperialism or small countries that appear to be peripheral. So the burden falls on you to figure out what happened historically, and then to forgive them even though they never articulated their own lack of understanding.

AK: Yes. It was on me to ask everything about the partition. In my family, nobody talked about the trauma they went through. You’d hear fragments of stories—like, “Oh, yeah, there was a bomb and we had to go into a bunker in the backyard.” And that story became weirdly normal. I still have my childhood imagination of what that looked like.

During my incarceration, I studied the partition and the history of India and Pakistan. I began to piece things together. I would call my mom or ask my sister to ask her, “Okay, wait, where were grandma and grandpa at this time? What area were they in before it was Pakistan?” My grandpa was twenty-one and joined the military; my grandma was a bit younger. I learned that she had to escape from her village. Some of her Hindu friends told her, “They’re going to come kill you in the morning, you have to leave.” So my grandma, her sister, and their mother escaped in the middle of the night through the marshes and creeks. They carried poison with them out of fear of being raped; they’d rather commit suicide than be dishonored like that or dishonor the family.

When I heard these stories, I started to think, Whoa, did Grandma really have to go through that? Maybe that’s why she seems so crazy. I started to pinpoint and investigate the trauma my family had been through and connect the dots to 1947, to the eight children they had.

There was another war in the seventies in eastern Pakistan, which ended up being Bangladesh. My mom and my uncles and aunts went through that; my grandpa was fully in the military by then. Then you have my parents’ marriage, and then me, and then America, and then the divorce. And you learn that America also has its own cultural history and intergenerational trauma with indigenous people and the ancestry of enslaved people.

AW: Did you have other South Asian or Pakistani friends in prison that you could talk to about this, or was it all through your family?

AK: Both. The Asian Pacific Islander community in prison has risen, sadly, by 250 percent in the last twenty or thirty years. There’s a lot of Vietnamese people in prison in California, at least where I did my time. There’s a huge population from Cambodia, from Laos. You can link that to intergenerational trauma once again; systemically, America clearly shows up in that space. Look back at the seventies, the Vietnam War, the refugee camps in Thailand and Laos and Cambodia. I learned about this history with my friends in prison. We learned it together. We taught each other about our histories.

I was fortunate to be in San Quentin Prison, where they had the ROOTS (Restoring Our Original True Selves) program. Its volunteers are from the AAPI community, and we would go through the cycle and learn, for example, about Vietnamese history. The people who were incarcerated would tell their stories; older incarcerated people told us stories of their time. “I went through this war and then I came to America as a refugee and then I was treated like shit.”

The South Asian population was much smaller in the prisons where I was. I did meet some South Asians who grew with me and rekindled my language, which I hadn’t spoken for so long, but it was still rare. For me personally, I’ve always lived two lives. When I step into home, it's shoes off; I'm fluent in my language, Urdu, and my culture. But when I was a kid, as soon as I stepped out, it was baggy clothes, hat backwards, pants sagging. I lived two different lives, and 100 percent of each was me.

After 9/11, I met more Muslims. But then Islam in South Asia is so different from Islam in the Middle East. I don't speak Arabic. Our culture is very different.

MK: I have an incarcerated client right now at CHCF [California Health Care Facility, a prison in Sacramento] whose parents met in a refugee camp in Thailand; his grandfather fought for the CIA in Laos. It’s exactly like you were saying; he joined a gang to seize control of that intergenerational trauma.

AK: Right. Most of the people I've spoken to were “gang” members when they came to America. So here's a five-year-old who just left the war in Laos and escaped to Thailand in a river with his mom. And then through whatever program he comes to America and grows up in a very poor Black and brown neighborhood, where he gets bullied. He doesn't speak English and he doesn't understand why he's going to this place called school, sitting in a class, not understanding a thing, and then getting beat up in the hallways and getting made fun of.

And then he runs into other Asian kids. If he's Vietnamese, there's another Vietnamese kid going through the same thing. They team up and they find other Vietnamese people. Other kids who are also getting beat up. So they become a gang and they learn a little more English. And then they fight back collectively—violently, because they've been taught violence. Violence is the solution to survival, right? That's how it is. You go through this war, go to a refugee camp, come to America, get bullied and beat up and assaulted, find people like yourself. Then it's called a gang. But that’s the life that empowers you. It gives you safety. And then you get the gang enhancement when you get incarcerated. It’s just cycles and cycles of violence. It's so sad.

How do you stop a cycle? You can try to stop it on both a systemic level and an individual level. My wife and I have a healthy relationship; I'm in a healthy place, she's in a healthy place, and that’s being inherited by our child. I’m breaking the cycle very loosely.But breaking the cycle systemically is where it’s at.

Next week, in Part 2 (“I’ve Never Belonged to a Democracy”) Adnan discusses why learning the legislative process in California is so essential to any advocate. He talks about why he loves writing and how it served as therapy on the first day in a cell at eighteen. He shares how “determination through spite” drove him to succeed, and how that spite evolved into empathy, healing, and understanding for those in his life who hurt him—and more broadly for humanity. And he shares his hopes for his baby boy, who was born last year.

Links for the week

Adnan has written elsewhere about the circumstances of his crime and the charge of felony murder, so we didn’t delve into it in here. You can read his own words at The Marshall Project:

In March 2003, I agreed to commit a crime. The plan was for me to grab some marijuana and run. No weapons were to be used. If so, I would not have agreed to it. I thought no one would call the police for stealing their weed, and that would be the extent of the harm. I never imagined a death.

For those new to the concept of felony murder, we recommend the lucid primer on mens rea (“guilty mind”) by Gideon Yaffe, a scholar of philosophy and law, in this New York Times op-ed:

As a legal principle, mens rea means that causing harm should not be enough to constitute a crime; knowingly causing harm should be. Walking away from the baggage carousel with a suitcase you mistook for your own isn’t theft; it’s theft only if you knew you didn’t own it. Ordinary citizens may assume that this common-sense requirement is already the law of the land. And indeed law students are taught that prosecutors must prove not just that a defendant did something bad, but also that his frame of mind made him culpable when he did it.

And yet, Yaffe explains, “felony murder” does not require proof of mens rea:

Democrats should push for even more sweeping changes to unjust “felony murder” laws, which permit murder convictions for anyone participating in a felony in which someone dies, even if no one involved could have been expected to foresee that happening. We know that adolescents are far less aware than adults of the risks their conduct involves, but since felony murder does not require proof of mens rea, adolescent defendants can’t offer evidence of their distorted perceptions of risk.

Public defenders Avi Singh and Sajid Khan host the podcast Aiders and Abettors. Last year they interviewed Adnan in a wide-ranging conversation that explored COVID in prison, the felony murder rule, restorative justice, and more.

Here’s Adnan’s episode of Ear Hustle, a podcast founded and created at San Quentin Prison by Nigel Poor, Earlonne Woods, and Antwan Williams. Adnan shares the story of his first visit from his mom, thirteen years into his incarceration:

Nigel: Wait, wait. How did you practice? How did you choreograph a hug?

Adnan: Because I haven't hugged someone in a long time—maybe by then it was thirteen years—I didn't know if my hand goes around her shoulder or her neck. I didn't know if it went diagonally, like two 45-degree angles. And, then I was like, "You know what, I'll let her lead." [...]

Nigel: Did you actually practice hugging somebody else?

Adnan: My cellie wasn't up for that. Nah. I did not. I just kind of air-hugged myself. And I didn't know exactly—like, "Uh, okay, what do you do? Up? Down? Is it sideways?" So, that was what I was nervous about.

We are so thrilled to see the brilliant and fearless Lina Khan appointed the chair of the Federal Trade Commission. For a good primer, see Matt Stoller’s most recent piece, “The Antitrust Revolution Has Found Its Leader.”

Book Club: Paradise Lost, Friday, June 25th at 3 PM ET.

We had so much fun at our last book club! Special shout-out, once again, to the Milton lover who joined us from Kuala Lumpur (at 3 AM, no less!). We’re glad to continue reading Paradise Lost. The excitement about Eve was infectious, so our plan is to focus on her character in our next discussion. As always, feel free to swing by, and don’t feel like you must read in order to attend. Email us at ampleroad@substack.com for the zoom link.

Gina, our resident expert, shares a quick guide for where to find the passages on Eve:

The first 400 lines or so of Book 5 also feature Eve.

If you're short on time, the Adam and Eve part of Book 4 begins at line 288. Book 4 begins and ends with Satan but it’s really well worth it, I think, in terms of rounding out his character.

Book 8 is mostly Adam and Raphael chatting, first about the cosmos and then about Adam's nativity. Eve herself is only present at lines 39-63, although you might want to know what Adam says about her first to God and then to Raphael (picking up around 354 and running through the rest of the book).

Book 9 is a must-read, of course. (Drum roll.)

We see Eve again in 10 (7-208, 863-end) and 12 (594 to end) if you want to know how the story ends.

Finally, we so appreciate all your responses to our recent letters about moving to Taiwan, marriage, assimilation, and belonging. Keep them coming, and thank you for helping us create such an authentic community here.