A Poignant Event Mourns Taiwan's Execution of an Innocent Man

Plus, our upcoming events in Taipei; and, a shout-out to our friend Eric Chung, who's running for office in Michigan

Albert and Michelle here. We were in Tainan over the weekend for a poignant 25-year anniversary of Lu Cheng’s execution. It was organized so lovingly, with such thought and care, by the Taiwan Innocence Project. The event featured a screening of Tsai Tsung-Lung’s documentary Formosa Homicide Chronicle II: The Case of Lu Cheng (島國殺人紀事2), followed by speeches and a candlelight vigil. The Innocence Project also prepared a table of Lu’s favorite snacks for us to eat. Our six-year-old munched on a Taiwanese equivalent of Cheetos, while we ate poria cake, which is chewy, lightly sweet, and made of rice flour.

Movingly, the Taiwan Innocence Project had organized the event in Erkong Military Dependents’ Village—now a cultural park, but once the neighborhood where Lu and his family lived. Many of Lu’s childhood friends were there: people who had grown up alongside him, who still remembered him as a boy. The familiarity of the place lent the evening a quiet gravity. It was also a beautiful, balmy night, perfect for an outdoor film.

*

The case of Lu Cheng remains one of the most complicated—and tragic (and frankly, ridiculous!)—episodes in the history of Taiwanese criminal justice. It involves forced confessions, spirit mediums, and staged reenactments.

The case refracted many of the ethnic and social tensions in southern Taiwan and unfolded during an intense period of democratization, when the institutions of justice were still catching up to the ideals of a new political order.

There are plenty of twists and turns in this story, and we’ll do our best to do justice to them. For an excellent English-language report, see Suvam Pal’s video available at Taiwan Plus, which was shared widely on social media. If you read Chinese, the best write-up is this article, written by Ze-Yu Huang and Yunching Ko at Story Studio.

The story begins in December 1997, when Chan Chun-tzu (詹春子) left her small advertising office in Tainan just before dusk to collect late payments from clients. She told her husband she’d be home for dinner. She didn’t return.

That night, her husband, Tseng Chung-hsien (曾重憲), received a phone call. A stranger’s voice, speaking in “standard Mandarin” (標準國語), told him: 「你太太在我手裡,準備五百萬,不要報警,等我電話……」 — “Your wife is in my hands. Prepare five million dollars. Don’t call the police. Wait for my next call.” In Tainan, where most people speak Taiwanese Hokkien or accented Mandarin, that kind of polished, standard pronunciation would have stood out—marking the caller as possibly from a mainlander minority. The man never called again.

Two days later, the following afternoon, a passerby spotted what looked like a pair of human legs on a hillside beside an industrial road in Longqi Township, Tainan County (now Longqi District, Tainan City). After the police were called, the body was confirmed to be that of Chan. The forensic examination determined that she had been strangled with a thin cord.

For at least a month after the murder, police had no clear suspects, and the case appeared to have stalled. The authorities came under intense media scrutiny and mounting political pressure to deliver results. The local police, already on edge, were operating in a climate of public anxiety shaped by a series of shocking violent crimes. In the 1990s, Taiwan had just emerged from martial law and was experiencing rapid political and economic transformation—booming stock markets, the first direct presidential election, and per capita income surpassing ten thousand U.S. dollars. Yet beneath this atmosphere of prosperity lay deep unease. It is hard to imagine now, when Taiwan feels so safe, but the 1990s were marked by a string of sensational criminal cases: the Liu Pang-yu massacre, the murder of Peng Wan-ru, and the Wu Tung-liang case, all of which unsettled society and stretched law enforcement to its limits. The 1997 kidnapping and murder of Pai Hsiao-yen, the teenage daughter of a popular entertainer, was particularly traumatic: her brutal death and the police’s slow response transfixed the nation and exposed the fragility of Taiwan’s new sense of security. In the aftermath, Pai’s mother, the singer and television host Pai Ping-ping, emerged as one of Taiwan’s most vocal advocates for retaining the death penalty, a stance that profoundly shaped public debate in the years that followed.

*

In January 16, 1998, officers from the Tainan Fifth Precinct summoned Lu Cheng (盧正), a 29-year-old former security guard. He was married and the father of two small children. Lu had attended the same high school as Chan’s husband and owed the advertising firm a little less than three thousand dollars. Police told him they needed his help with the investigation.

He was taken to the precinct’s basement, to a small, windowless interrogation room, and held there for thirty-one hours.

Over those thirty-one hours, he was tortured. Initially, the police officers made him squat and stand, warning him that things would “get worse” if he didn’t confess. Then several officers took turns questioning him in shifts, asking the same things again and again: whether he had killed Chan, how he had done it, and why. Lu repeatedly denied any involvement. He explained where he had been on the day of the crime and insisted he had no connection to the case. But whenever his answers failed to satisfy the officers, they beat him. He was punched and kicked. Through the night, officers rotated in and out, forcing him to alternate between squatting and standing. Whenever he closed his eyes from exhaustion, blows followed.

He couldn’t make sense of what was happening. He had no idea why Chan had been killed, or what details the police were pressing him to produce. Fear and fatigue built up hour by hour, feeding a growing sense of helplessness.

Throughout the interrogation, Lu continued to protest his innocence and begged for help, but each attempt failed. The combination of threats, cajoling, and promises slowly wore him down. Police told him that if he kept denying the charges, he would face harsher punishment later. They also told him that if he confessed quickly—“acknowledged his mistakes,” in their words—he might qualify for leniency as a voluntary surrender, bringing the case to an end and sparing his family further worry.

Enter the spirit medium. What finally broke through to him—besides the torture—was the presence of somebody he trusted. The spirit medium, Pan Min-chieh, was the wife of one of Lu’s former high-school teachers. She claimed to possess spiritual abilities and had long assisted police in “spirit-guided” investigations. She was present from the very first interrogation—not as a police officer, but as a private third party with no official role in the case.

Tapes from the interrogation show that Pan played a crucial role in persuading Lu to sign the confession. As Chien-Jung Chien, a judge of the Taiwan High Court, later wrote, “I think Pan Min-chieh’s function in the room wasn’t her so-called ‘spiritual ability,’ but her identity as a clerk at the Tainan District Court. Lu believed his teacher’s wife understood the law, that she had connections, and that she would never harm him. So he followed her cues, taking her handwritten notes and repeating what she told him: ‘I came to turn myself in. I know I was wrong.’”

Lu may have believed that if he followed her instructions, he would be transferred out of police custody and into the “court,” where his teacher’s wife could protect him. He may even have been told—or come to believe—that confession was the only way to survive, and that, if he admitted guilt, he could ensure his unseen family would not be arrested or harmed.

Pan later testified that when she arrived at the station, Lu had insisted on his innocence and told her he was being beaten by officers. Her statement should have counted in his favor, but the court neither investigated nor accepted it.

An aside about this spirit medium: you might be wondering if she ever came to be ashamed of her role in getting him executed. Absolutely not. The clip above shows how this spirit medium became something of a local celebrity and is credited with having aided the “successful” resolution of multiple cases. (And, as Lu Cheng’s sister pointed out at the event, Pan is collecting a full pension for her work as a government clerk.)

Lu Cheng’s case has since become a landmark in Taiwan’s contemporary debate over the death penalty. What made it so controversial was not only the weakness of the evidence but also the haste with which the execution was carried out.

There were no matching fingerprints. The confession had been extracted under torture and duress. Portions of the interrogation tapes were missing, even though police had already begun recording such sessions as part of new procedural reforms. Key evidence was contradictory or incomplete, and the Control Yuan was still reviewing the case when the Ministry of Justice signed off on Lu’s death warrant.

On the evening of September 7, 2000, the Taiwanese state executed Lu Cheng. Hours earlier, his family had told him to keep faith: the Control Yuan—Taiwan’s constitutional watchdog—had opened an inquiry into his case and requested the files. The files were never fully delivered. Up until his last moments, as the executioner who shot him has recently revealed, Lu maintained his innocence. His last recorded words to the prosecutor were simple: “I am innocent.”

Within anti–death penalty circles, Lu Cheng’s case came to symbolize everything that could go wrong in a system driven by pressure to produce convictions: a confession obtained through coercion, and a state apparatus unwilling to pause, even briefly, to re-examine its own work. As Lin Hsin-yi, one of the founding members of the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty (TAEDP) and its Executive Director, remarked, it was the Lu Cheng case that pushed her to dedicate her life towards anti-death penalty activism.

*

All commemorations make you think about the passage of time, but this one especially.

Tsai, who shared his thoughts after the screening, filmed Formosa Homicide Chronicle II (2001) one year after Lu’s death. On screen, we caught glimpses of a much younger director reacting, often with incredulity and disbelief, to claims made the prosecution.

After the screening, Tsai spoke with contrition. “I know this is not a perfect film,” he said. “It has many shortcomings.” Yet he was grateful he’d managed to document that moment in Taiwan’s history—the rawness of the emotion, the strangeness. What heartened him was seeing how many young people today support Lu Cheng—people who were just kids when Lu Cheng was executed. He thanked people like Shih-hsiang Lo and Yunching Ko, the director and deputy director of the Taiwan Innocence Project, and all the other representatives of the NGOs who came. “To be honest,” he continued, “I was very lonely when I was making the film.”

The film also captures a Taiwan that no longer exists. The opening aerial shot of Er Kong Military Dependents Village reveals a slum and shanty town. You’re reminded how poor the area was—and how disconnected its people must have been from the court system. The film never makes it explicit, and nor did the commemoration, but Lu Cheng came from a much more disadvantaged background than his victim. We see shots of a small room that Lu shared with his brother.

Twenty five years later, the economic transformation of his neighborhood feels stark. We watched the film on a beautiful autumn night, surrounded by newly built high rises. The juancun, once a slum, had been converted into a cultural park. Sanitized, its surrounded by small independent shops selling gifts. It has the same vibe as the renovated cultural parks now dotted across the country. It’s nice.

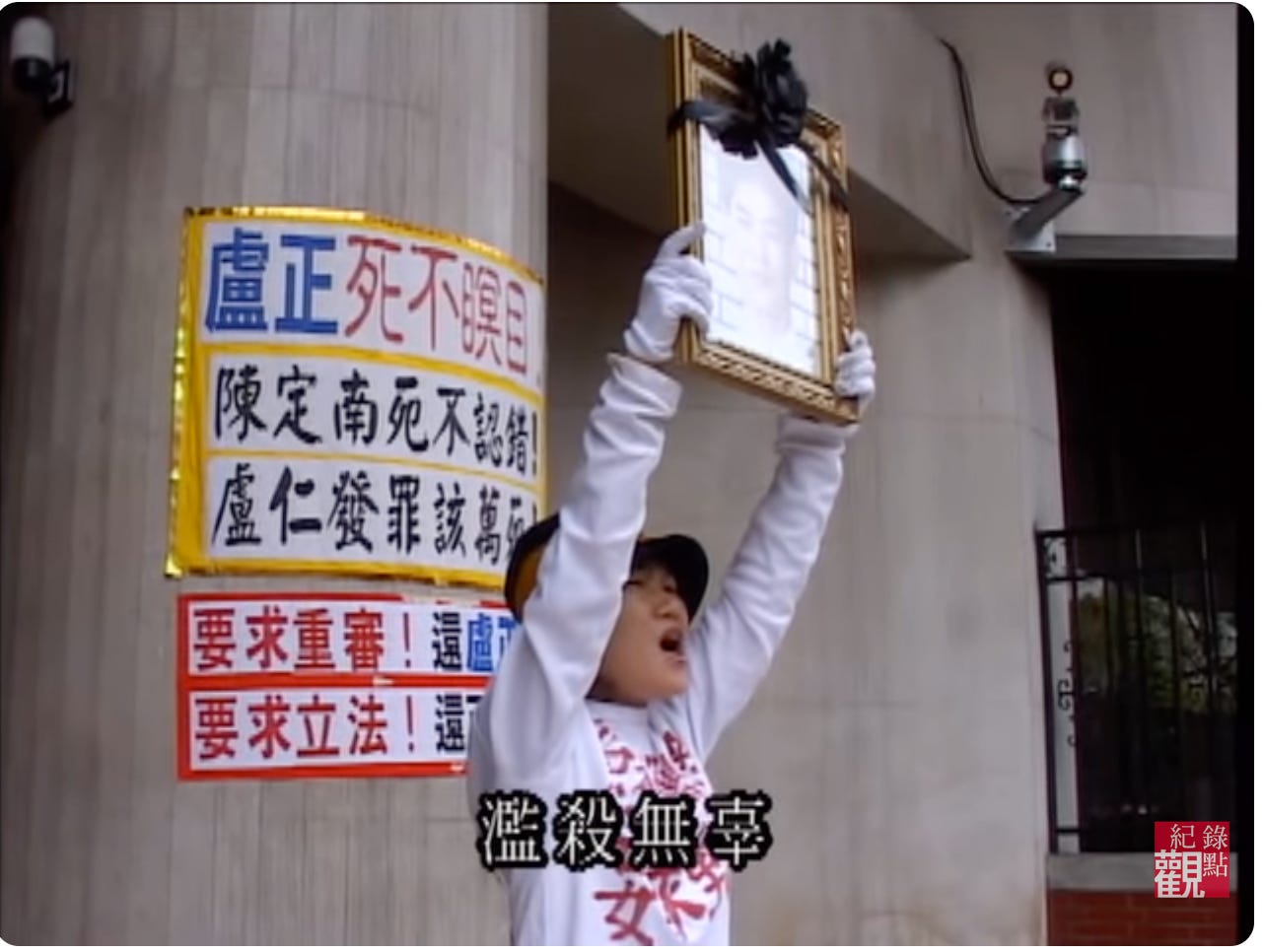

The heart of Tsai’s film is Lu’s sisters, Lu Jing (盧菁) and Lu Ping (盧萍). They are totally fearless, absolute badasses. You watch their relentless activism unfold. You see them faint when they hear the news of their brother’s execution. You see them march to the Ministry of Justice, demanding to see the minister, shouting his name. Staging protest theater. Performing religious rituals. Sitting for hours. You see them camp outside of the Ministry of Justice—every day for two months. They wail, they scream, they sob without restraint. Something about their power to channel raw emotion—to curse, to speak prophecy, to name evil—calls to mind characters of an ancient Greek drama.

And then, as time presses on, you watch these women learn legal language and become advocates for judicial reform—pushing, for instance, for all police interrogations to be recorded. You see them visit the tomb that holds their brother’s ashes, blessing him with birthday cake and his favorite snacks. Their devotion. Their determination to clear his name. And in all these scenes, you consider how lonely their battle must have been. More often than not, their protests are a party of two.

In the 2001 film, the two sisters seem alone, with hardly any advocates. Even though there exist sympathetic voices within the legal system, you rarely see any non-Lu family members show up to support their cause on the street. In one scene, a well-meaning but inane bureaucrat tries to convince them to give up their fight because their brother is already dead, and only God can help them now. Why not just call it quits?

Yet on Saturday night, the institutions that people created in the past 20 years have provided community and created change. Young volunteers—many born after Lu’s death—show up to pay tribute to a person killed by the state. We were moved by the solidarity between exonerees and the families of the wrongfully convicted. Hsieh Chih-hung (謝志宏), who spent nineteen years on death row and was exonerated, brought some of the best noodles and duck blood from Tainan. The older sister of Lu Chin-Kai, who spent 20 years in jail and was finally exonerated this fall, came to support the event. She said she’d never been to Tainan, and it was her first time taking the High Speed Rail. But she wanted to be here. Then she spoke directly to the two sisters, who sat in the front. “Only we families know how hard it is,” she said. “The type of hell we’ve gone through.”

The sisters replied, “You all give us so much strength.” Yet of course the same could be said about them. Unapologetic and undeterred, they wear their hearts on their sleeves. It’s clear they never backed down and never will. If you see clips of them or meet them in person, it’s impossible not to admire them. We all have something to learn from the way they refuse to bow their heads or give up. Amidst all the social and economic changes of their neighborhood and country, their dedication since his execution has not changed.

It’s been a bad year for activists working on criminal legal reform in Taiwan. Last September, the Constitutional Court upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty. In January, Taiwan executed a death row inmate for the first time in over five years. At the commemoration, a member of the Judicial Reform Foundation said they’ve been watching things slide backward. But if the sisters remind us of anything, it’s that this won’t be easy, and they’re not going anywhere. This is going to be a long fight.

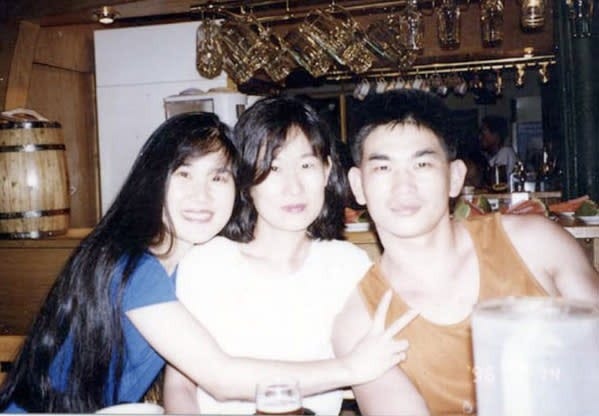

And of course, the most poignant reflection of time: Lu Cheng himself. The sisters showed a slideshow of photos from just before he died. One of him in uniform—young, athletic. Another in sunglasses—in another life, he might have been a Taiwanese James Dean. His time stopped. He never got to see how everything changed, never got to grow old.

Invisible Nation

Thanks to people who listened in on my conversation with three brilliant women: Stacey Abrams, Representative Jasmine Crockett and Vanessa Hope. We talked about Hope’s film Invisible Nation (see our review) and how struggles to preserve democracy are always interconnected. Thanks to Together Films for organizing. You can watch the discussion here.

A few upcoming events

All events are free and open to the public. Looking forward to seeing you there.

On November 11-12, the Institute of History and Philology will be hosting a great workshop, “Doing Chinese History in Taiwan and around the World, 1985-2025.” The workshop includes an all-star lineup, including a keynote by Professor Dorothy Ko, and a talk by Sebastian Veg (whom we interviewed a couple of years ago).

On Thursday, Nov. 13th at 7 P.M., at Touat Books, Michelle’s moderating a discussion on the death penalty between Carol Steiker, renowned professor at Harvard Law School and a passionate advocate of abolishing the death penalty, and Chuanfen Chang, one of Taiwan’s most acclaimed writers of her generation and the chairwoman of Taiwan Alliance Against Death Penalty (TAEDP). The discussion will be in both English and Mandarin.

Carol Steiker has two talks in Taiwan that have been organized by Chengyi Huang at Academia Sinica:

On Tuesday, November 12th, 14:00 to 16:00: “The Prospects of Worldwide Abolition of the Death Penalty” at Academia Sinica. This will be moderated by the law institute’s director Chien-Liang Lee, and the discussant is lawyer Nigel N.T. Li, a lifetime advocate for abolition in Taiwan.

On Wednesday, November 13th, 10 AM–12 PM: “Challenges Facing Justice Reform in a Time of Political Backlash” at National Taiwan University College of Law. This will be moderated by Jade Hsu, former Constitutional Court justice, with Professor Kai-ping Su, who teaches at National Taiwan University College of Law, as the discussant.

On Saturday, Nov. 22nd at 7 P.M., Michelle is speaking at New Bloom/Daybreak at 7 P.M. on a panel with Brian Hioe, Michael Fahey, and Elizabeth Hsinyin Lee about graphic novels, manga, and children’s books from Books from Taiwan.

On Sunday, Nov. 23rd, at 2:30 P.M at Human Space Roosevelt, Michelle’s speaking with Amnesty International about her book Reading with Patrick and, more broadly, literature and incarceration. (Thank you Naomi Goddard for organizing!) Discussion in English.

Eric Chung running for Congress in Michigan

I met Eric Chung seven years ago and was struck by his warmth, curiosity, and passion for social movements. Amidst all the depressing news, I’ve found hope in his campaign running for Michigan’s 10th Congressional District (northeast of Detroit). MI-10 is one of the only open swing seats held by a Republican that was decided by 0.5% (1,600 votes) in 2022 after the Republican outspent the Democrat $7 million to $1 million.

Eric grew up in the district as the son of a Macomb County autoworker and Vietnamese immigrants. His parents later served in the Commerce Department, working to bring back jobs and revitalize manufacturing in their community after the chip shortage derailed the Michigan’s auto industry. Eric also helped confirm Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court as a special counsel for Senator Durbin and the Senate Judiciary Committee. He broke a record for the district by raising over $600K in a quarter (#1 in the country for a first-time candidate running for a competitive seat and #1 in the country for a POC or AAPI or LGBTQ+ challenger candidate), and has been endorsed by ten members of Congress. Please let me know if you would like to chat with him or are willing to support him here.

Book Club: Miranda July’s ALL FOURS

Our next book club is Friday, November 21st 7 PM EST / Saturday, November 22nd at 8 AM (Taiwan time: note it’s daylight savings!). We’re reading Miranda July’s All Fours. After that, we’ll read Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington and Percival Everett’s James. Thanks to our book club members for their suggestions! Please reply to this email for a zoom link.