FilmStack Inspiration Challenge Day 63: Two Takes of Contemporary Taiwan

We recommend two marvelous Taiwanese films, On Happiness Road and Au Revoir Taipei; plus a panel this week on Invisible Nation

Perhaps every film lover knows the story of the Taiwanese New Wave—that transformative moment in the island’s cinematic history when a new generation of directors catapulted Taiwan onto the global stage. This includes Hou Hsiao-hsien’s City of Sadness, Edward Yang’s Yi Yi, and, later, the “second-wave” meditations of Tsai Ming-liang. (See Michelle’s essay on City of Sadness at the Paris Review here.)

The Taiwanese New Wave first emerged in the 1980s, when a new generation of filmmakers rejected the formulaic studio melodramas that had dominated Taiwanese screens. Instead, they chose to turn the camera to scenes of everyday life, filming the streets, apartments, and uneasy silences of a rapidly changing society. Their long takes and understated realism gave shape to a new moral and emotional vocabulary. Attuned to the weight of history and the disorientations of modernity, their work has been immortalized in Taiwan, including in a wonderful manga, Local Heroes.

While the New Wave brought Taiwan unprecedented international critical acclaim—winning prizes at Venice, Berlin, and Cannes—it struggled to win over local audiences. Theaters often sat half-empty for masterpieces like A Brighter Summer Day or The Time to Live, the Time to Die. By the late 1990s, critics were hailing the movement’s artistry even as producers lamented that “nobody goes to see these films.” Most Taiwanese moviegoers still preferred Hollywood blockbusters to the austere realism of their own directors.

That began to change in 2008 with Wei Te-sheng’s Cape No. 7. No one expected a modest, locally produced romantic dramedy to rewrite box-office history—but it did. The film grossed over NT$530 million, surpassing Titanic’s record in Taiwan and turning into a full-blown cultural phenomenon.

Cape No. 7’s success felt radical not just because it filled theaters, but because it shifted the center of gravity in Taiwanese cinema. Instead of Taipei’s urban angst, it turned its gaze toward the south. The movie focused on a sun-washed, rural seaside town alive with local music, dialect, and humor. Its nostalgic subplot, tracing a long-lost romance between a Taiwanese woman and a Japanese man during the colonial era, struck a chord with audiences hungry for local stories. Yet, it also sparked controversy. Some critics saw in its wistful tone a troubling idealization of Japan’s colonial past. Others, however, praised it as an honest reckoning with Taiwan’s layered identity.

Cape No. 7’s success signaled a new era. Around the same time, a new generation of filmmakers emerged, each finding fresh ways to tell local stories. Thomas Lin’s Winds of September (2008) offered a melancholic portrait of adolescent friendship; Cheng Fen-fen’s Hear Me (2009) brought social awareness to urban youth; and Doze Niu’s Monga (2010) depicted 1980s Taipei as a mythic battleground of loyalty and masculinity. The other megahit from that period, Giddens Ko’s You Are the Apple of My Eye (2011) captured an entire generation’s nostalgia. Along with Yeh Tien-lun’s Night Market Hero (2011), it appeared that Taiwanese cinema had found its footing again. More playful than the New Wave, it still felt deeply local at heart.

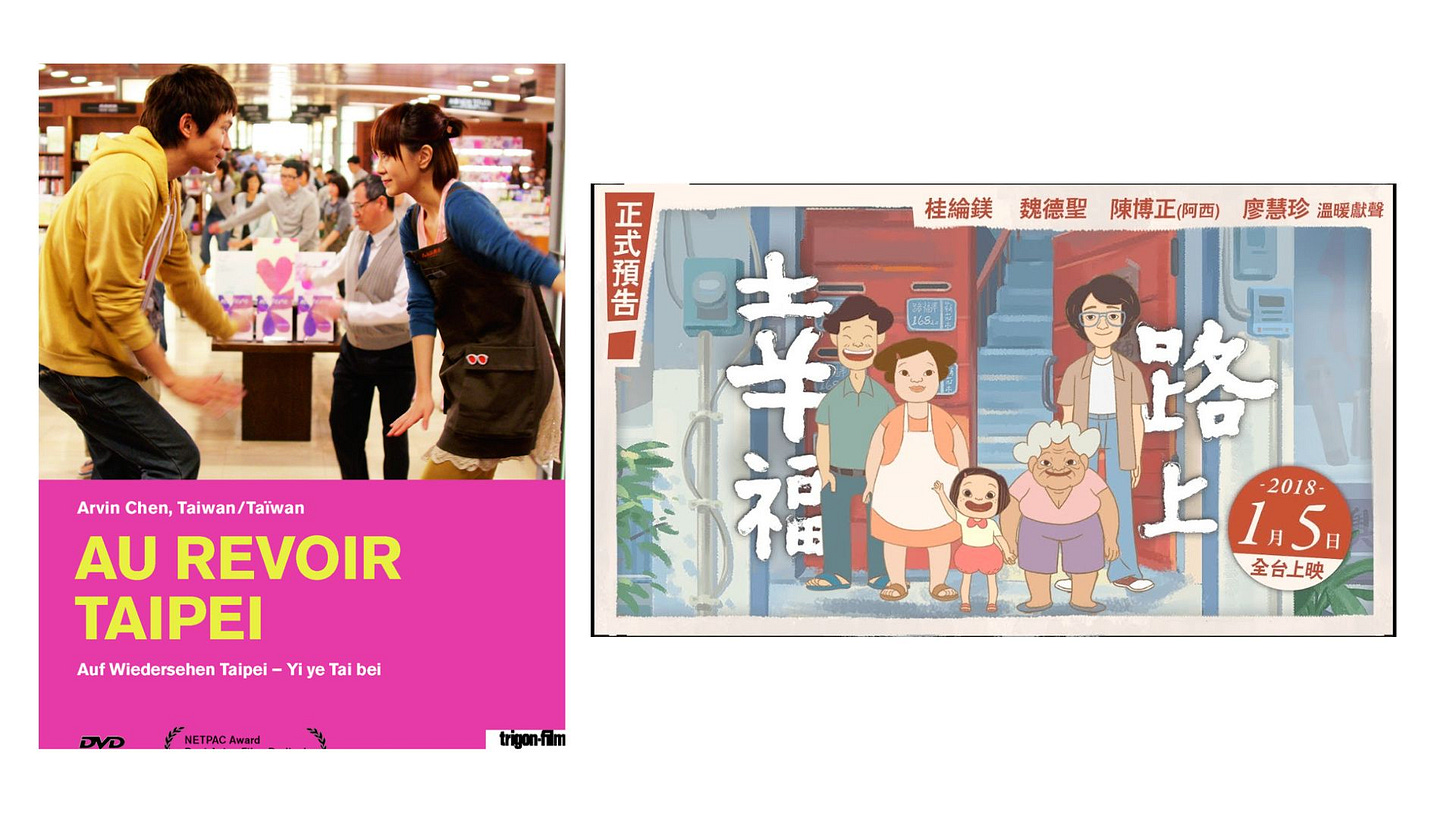

In today’s post, as part of the Filmstack Inspiration Post Challenge, started by the wonderful Ted Hope, we recommend two films that have inspired us. Both come from what scholars have called the Taiwan Post New Wave moment: Au Revoir Taipei (2010) and On Happiness Road (2017).

Arvin Chen, Au Revoir Taipei 一頁台北 (2010)

Arvin Chen’s directorial debut, Au Revoir Taipei (2010), is a romantic comedy that lingers on the countless ways Taipei enchants us. The film follows Kai, a young man who spends his nights studying French to reunite with his girlfriend in Paris, only to find himself drawn into a low-stakes underworld of small-time gangsters, policemen, and a bookstore clerk, Susie, who quietly changes the course of his life. What begins as a simple errand for quick cash turns into an all-night chase through Taipei’s alleys and noodle stalls, a wry and luminous portrait of urban loneliness and connection.

The influence of Edward Yang is unmistakable. Chen, who grew up in California and studied architecture, apprenticed with Yang early in his career, an experience that redirected his life toward filmmaking. From Yang, he inherited a deep attentiveness to Taipei’s textures. Yang once put it this way: “ I consider myself a Taipei guy. I’m not against Taiwan. I’m for Taipei. I wanted to include every element of the city, so I really gave myself a hard time, to build a story from the ground up.”

Yet Chen diverges from his mentor in tone and temperament. Yang’s films, famously inspired by his own encounter with Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God, which led him to abandon a career in engineering, are anchored in philosophical seriousness. His characters wrestle with the weight of history and the tensions between tradition and modernity, between “East” and “West.”

Chen’s world is lighter and more playful. His characters seem less burdened by history’s gravity and more caught up in trials and tribulations of the present. His style, both absurd and tender, unfolds like a collage. There are snatches of screwball timing, fragments of bittersweet love, and something ineffably personal holding the pieces together. Au Revoir Taipei feels as influenced by Twin Peaks as by the French New Wave, a whimsical portrait of a city where love, confusion, and hope clash together.

The film captures some of the indelible textures — and the quiet bizarreness — of Taipei. A son works alongside his parents at a street-side noodle stall; police stake out hidden goods tucked inside the incense burner of a temple. These small moments evoke a city that is at once ordinary and enchanted, full of gestures that feel both familiar and faintly surreal. It also has a hilarious chase scene set in Taipei’s subway.

And really, can you think of a better shot of a Taipei interior than this one?

The scene shows a Taipei apartment that feels both lived-in and slightly unreal. Warm light falls across patterned tiles, a glowing fish tank, and a folding screen painted with peacocks, while a small television flickers in the corner, its blue light cutting through the room’s amber glow. The space feels cramped but intimate, the décor of another time meeting the technology of the present. It’s the kind of interior Arvin Chen returns to again and again: layered, a little melancholy, and eccentric. His Taipei isn’t sleek, but rather layered with traces of different times and lives.

Perhaps most movingly, Chen’s film captures the quiet frustrations of young people in Taipei — their exhaustion, their stalled ambitions, their uneasy balance of work and family. We see the long hours, the cramped apartments, and the reluctant returns to parents’ homes brought on by high rents, low pay, or the invisible weight of expectation. Yet alongside these pressures, Chen finds something gentler: the awkward tenderness of youth, the uncertainty that coexists with unshakable hope and desire. His characters drift, hesitate, and dream.

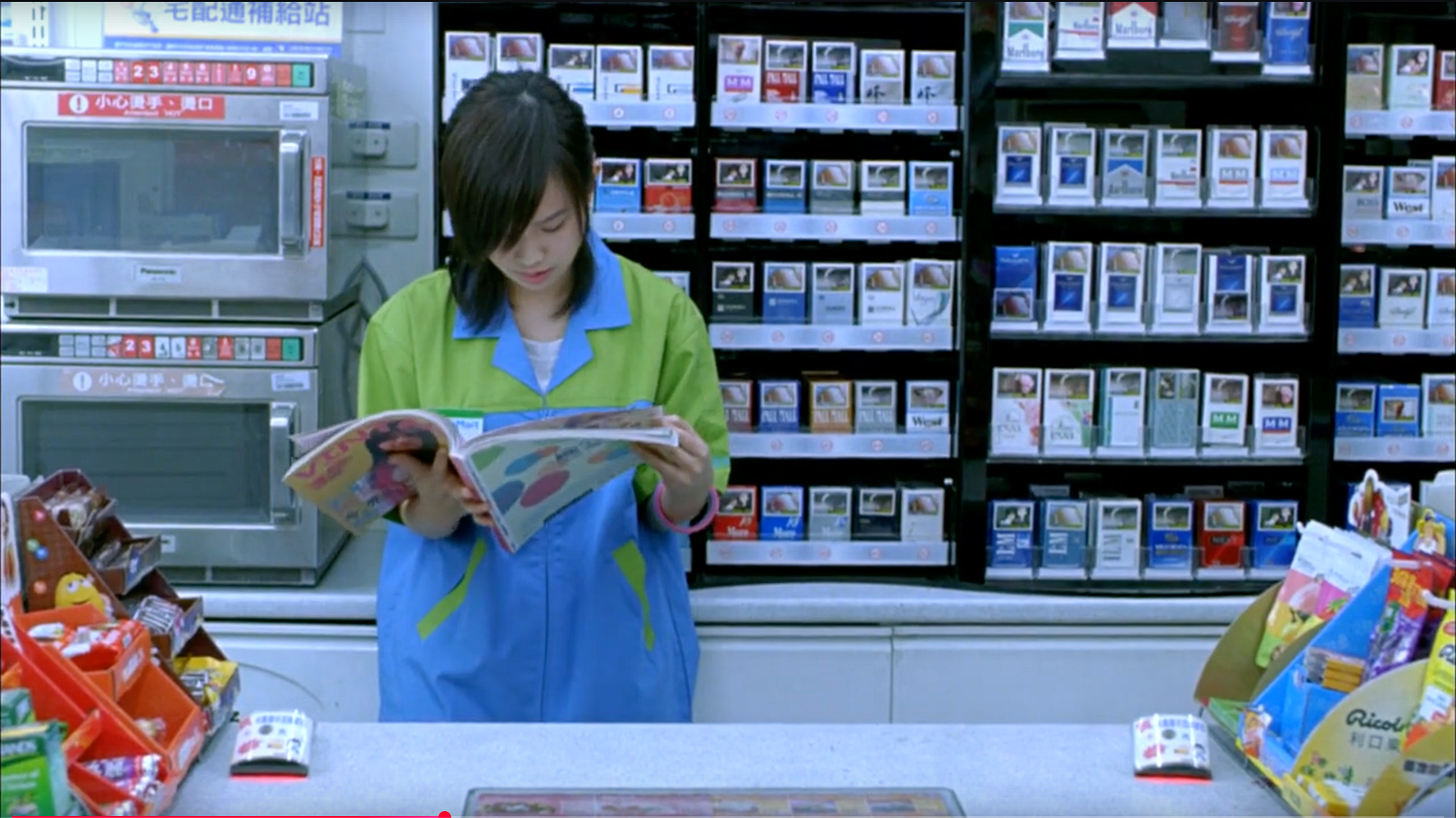

And who can forget the dreams of those local convenience store clerks. (For anyone who’s been to Taiwan, you’ll know how inescapable those stores are.) Inside one, a clerk flips idly through glossy magazines while his co-worker looks on, pining after her.

Also unforgettable are the small-time gangsters, eager to please their boss, who dreams only of retiring and eloping with his lover to Hainan Island.

The boss warns his underlings not to be so enterprising, to play it safe — a line that earns one of the finest eye-rolls ever caught on film.

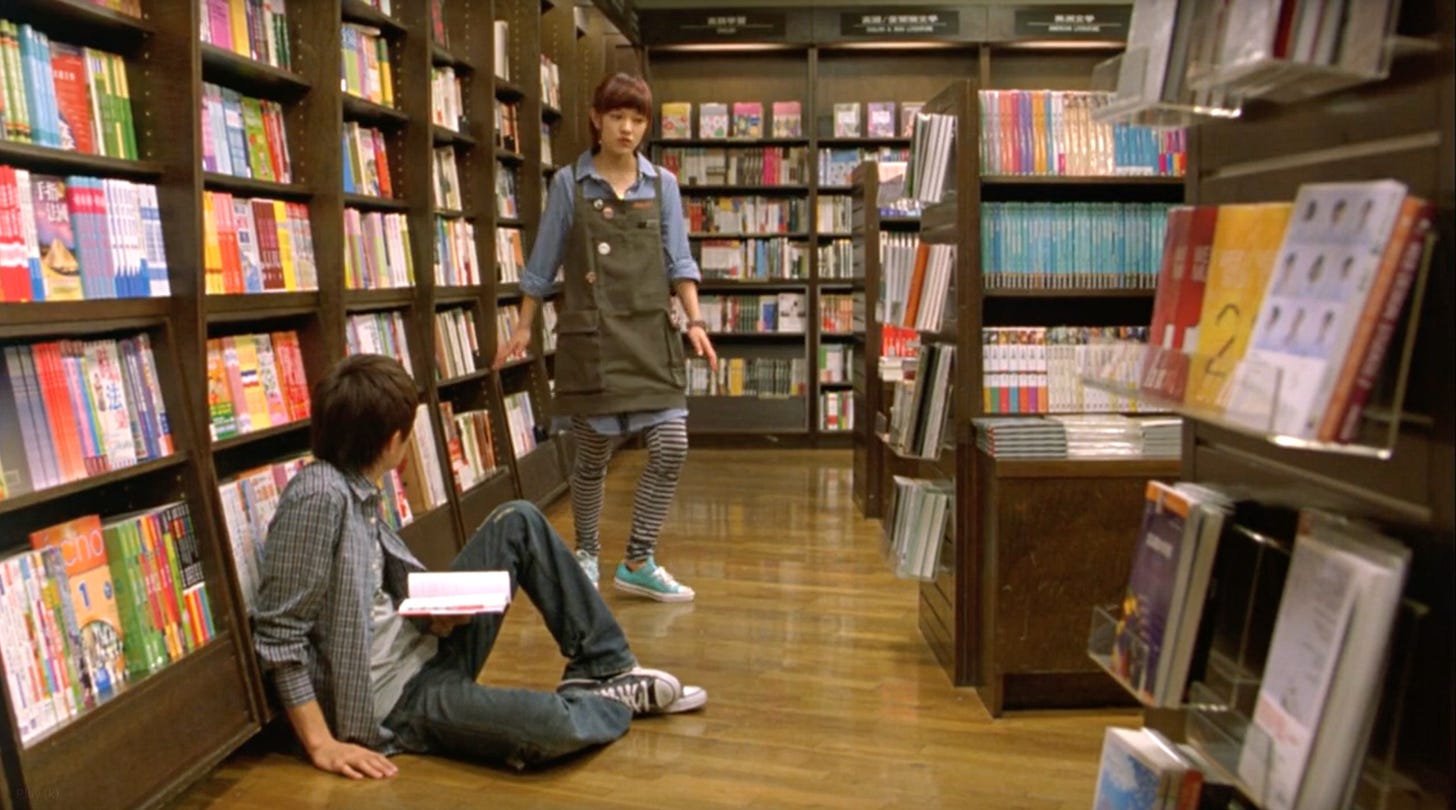

And finally, who can forget this scene? Susie, the bookstore clerk, has begun to notice our hero Kai, who comes in every day to study French from the store’s textbooks.

“Hey,” she asks, “have you ever thought about taking classes?”

“Umm…” Kai hesitates, too shy to answer.

“Like me! I’m taking classes now. Have you ever heard of Lindy Hop?”

“The what?”

“It’s a kind of swing dance.”

“Ummm…”

“Oh! Maybe I can just show you. It goes something like this…”

In the end, Chen reminds us that amid the world’s small defeats and quiet absurdities, sometimes the best response is just to dance.

Sung Hsin-yin, On Happiness Road 幸福路上(2017)

“When I wake up,” says Chi, an immigrant to the United States, “I often forget where I am and who I am.” Chi came from Taiwan to study, found a job, and got married. Not long after her marriage falls apart, she learns that her grandmother back in Taiwan has passed away. Now in her mid-thirties, Chi returns home.

This is the plot of On Happiness Road, a warm and poignant Taiwanese animated film propelled by that universal question, “Who am I?” Released in 2017, it was written and directed by Sung Hsin-yin. (We have written about her recent film Lost in Perfection.) From class consciousness to Indigenous culture, from intergenerational conflict to democratization, On Happiness Road weaves together many aspects of contemporary Taiwan effortlessly, without ever feeling didactic or forced. It’s a political film, yet one that feels expansive, human, and deeply inflected by a woman’s perspective.

Early in the film, when Chi returns to Taipei, she finds herself sitting by a fire, roasting meat and vegetables, surrounded by her mother and aunties who bombard her with questions, advice, and unsolicited commentary.

“How much money do you make a year in America?” one aunt asks.

Another chimes in: “Your kids will be American by birth.”

Then her mother praises a woman whose son has become a successful banker in the United States.

“What’s the point?” comes the sad reply. “We hardly ever see him, and my grandchild only speaks English. She can’t even say the word Grandma.”

But we also glimpse the son’s story. While in the United States, Chi visits her cousin and asks him if he truly can’t come home for the funeral. He says he can’t get time off work and gives her gifts to bring back to Taiwan. Meanwhile, he tries to coax his young daughter into eating her shuijiao—dumplings, in Mandarin.

“I don’t want buns!” she yells in English.

“They’re not buns—they’re dumplings!” he replies.

It’s unclear what frustrates him more—her refusal to eat, or her inability to tell buns from dumplings.

The film captures the ambivalence of a generation taught to leave Taiwan in search of a better life. But is that life truly better? Is it happier?

On Happiness Road switches between flashbacks of Chi’s childhood and her present-day life. Born in 1975, on the exact day Chiang Kai-shek died, Chi grew up during the final decade of martial law. The most moving scenes reveal how the school system, run by the Kuomintang regime, powerfully shapes her relationships with her family.

In one sequence, she awaits eagerly for the arrival of her grandma, an Indigenous woman who takes the daylong journey from Hualien, the beautiful yet remote eastern coast of Taiwan. When they reunite, they are like joyful playmates. Once she’s settled in, Grandma says to her, “Buy me a pack of betel nuts.” Betel nuts, a stimulant somewhat comparable to tobacco or cocoa, are chewed today famously by truck drivers trying to stay awake on long shifts. Little Chi runs off to buy them, only to be told by the woman at the stand, “Only savages and loose women chew betel nuts.” At school, word spreads that Chi’s grandmother chews them, and her classmates begin to taunt her: “Savage! Savage!”

Chi says nothing to her grandma. But over dinner a few days later, she says to her grandma, “Have you ever chopped off a man’s head? It says in my textbook that indigenous people in Alishan chop off men’s heads.” Her mother and grandmother burst into laughter at first. But the mood shifts when Chi continues, “My classmates said only savages chew betel nuts.”

At this her mother turns to her grandmother—now we see a glimpse of another intergenerational battle—“I told you not to chew betel nuts in Taipei!” Her grandmother straightens and replies, “People can call us whatever they want.”

School affects Chi’s relationship with not only her grandma, but her father as well. Pointing to a picture of a sofa, the teacher—portrayed as a scolding, unhappy Han chauvinist—asks the group of first graders how to pronounce it. Chi raises her hand excitedly and says, “Phòng-î!” But that’s Taiwanese, not Mandarin, and the regime under Chiang Kai Shek suppresses all languages besides Mandarin. The other students laugh at her. The teacher berates Chi and informs that those who speak Taiwanese will be fined. “But my family doesn’t have any money!” multiple students cry out.

After school, Chi walks home and is chased by a stray dog. Her father swoops in on his motorcycle to rescue her. She’s overjoyed, and a lovely fantastical sequence pictures her father as a prince. But that evening, her father mispronounces the word “Chinese” in Mandarin—he only speaks Taiwanese. She laughs at him, correcting his pronunciation. Of course, it goes without saying—this is behavior she learned at school.

These moments carry a quiet, lingering weight: an adult is remembering the small, innocent cruelties she once directed toward her family. The film suggests that to excel in school under martial law required, on some level, a dismissal of the languages, perspectives, and experiences her family embodied.

And excel Chi does: she earns admission to the prestigious Beiyinu, Taiwan’s top girls’ school, and firecrackers are lit in her honor. Her parents, both factory workers, are ecstatic. They dream their daughter will become a doctor. But once Chi enters National Taiwan University, her focus shifts—she spends all her days at protests. It is an exhilarating time in Taiwan: martial law has just been lifted, and demonstrations erupt constantly. Chi decides not to pursue medicine, convinced she can change the world. Years later, reflecting on the course her life has taken, she says, “I always break my parents’ hearts.”

The story of this film also reveals something about Taiwan. When it was first released, a largely male circle of critics failed to recognize its brilliance. But as it began winning awards—from Taiwan’s Golden Horse to major prizes in Japan—it became a late-blooming hit.

We cried at the ending. We won’t spoil it, but it’s weepy and life-affirming. Just one last detail that we love about the film: Even though her grandma is dead, Chi continues to dream of her and speak with her. In one encounter, Grandma says, “It’s no fun for me in Taipei. There are no mountains,” before flying away on a rooster. (Anyone who knows Hualien, where Grandma is from—surrounded by mountains at every turn—will understand exactly what she means.)

And in another moment, Grandma appears when Chi is feeling lost.

“You’re all grown up. Why be afraid?” Grandma asks.

“You’re dead, and you still nag,” Chi replies—who is never surprised by these appearances.

And one more scene. Chi contemplates coming home for good and despairs at all her failures. But she remembers something her grandma said to her: “Being different will give you strength.”

Live Virtual Panel on Vanessa Hope’s Invisible Nation & Democracy

We’ve written before about Vanessa Hope’s urgent and powerful documentary on Taiwan, which has become a box-office success in Taiwan and made waves across the world. Invisible Nation captures both the extraordinary democracy Taiwan has built and the peril it now faces.

Ted and Vanessa Hope have partnered with Together Films to create a six episode virtual event series on protecting democracy. Please come to a virtual event Michelle is moderating with an all-star panel: Vanessa Hope, Stacey Abrams, and Jasmine Crockett. It’s this Sunday at 7 PM EST / Taiwan time 7 AM. We hope you’ll join us for an exciting event.

Here are the details:

Live Panel: Sunday, October 26 | 7pm ET / 4pm PT / 7 AM Taiwan time

Moderated by: Michelle Kuo, Author & Professor

Speakers:

Vanessa Hope, Director, INVISIBLE NATION

Stacey Abrams, Former Georgia House Minority Leader

Jasmine Crockett, United States Representative

Watch the Film Online: October 22–26

Use the code 1026INVISIBLE20TED at checkout to receive an exclusive 20% discount on a ticket

REGISTER NOW (click here)

Other Upcoming Events

On November 13th, Thursday at 7 PM, I’ll moderate a conversation between at Touat books between Chang Chuanfen, a renowned writer and chairperson of the Taiwan Alliance Against the Death Penalty (TAEDP), and Carol Steiker, a scholar and death penalty expert at Harvard Law School (and my very dear former teacher—she’s a legend and has a heart of gold). Professor Steiker will also be giving two major lectures earlier in the week; many thanks to Chengyi Huang (see our interview with him) for organizing:

Wednesday, November 12th, 2 - 4 PM (NOTE TIME CHANGE): “The Prospects of Worldwide Abolition of the Death Penalty” at Academia Sinica. This will be moderated by the law institute’s director Chien-Liang Lee, and the discussant is lawyer Nigel N.T. Li, a lifetime advocate for abolition in Taiwan.

Thursday, November 13th, 10 AM–12 PM: “Challenges Facing Justice Reform in a Time of Political Backlash” at National Taiwan University College of Law. This will be moderated by Jade Hsu, former Constitutional Court justice, with Professor Kai-ping Su, who teaches at National Taiwan University College of Law, as the discussant.

On November 22nd, Saturday, I’ll speak at Daybreak & New Bloom about Taiwanese comics, graphic novels, and children’s books and Books from Taiwan. I’ll be in conversation with Brian Hioe, Elizabeth Hsinyin Lee, and Michael Fahey and will be bringing a full suitcase of books. The time hasn’t been set yet, but feel free to reply if you’d like to attend.

Book Club

Our next book club is Friday, October 24th 7 PM EST / Saturday, October 25th 7 AM Taiwan time. We’re reading Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo. After, we’ll be reading Miranda July’s All Fours, Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington, Percival Everett’s James, and Natalia Ginzburg’s Road to the City. The book club is open to all paying subscribers. Thanks to our book club members for their suggestions! Please reply to this email for a zoom link.

Added Au Revoir Taipei to my watch list. Looks wonderful.

Wow. More great films to add to my “ToWatch” list. Thanks for this!