Hear Our Voices: An Interview with Radhika Natarajan

How Do You Talk About Anti-Imperial Struggle With Kids? (And Other Big Questions)

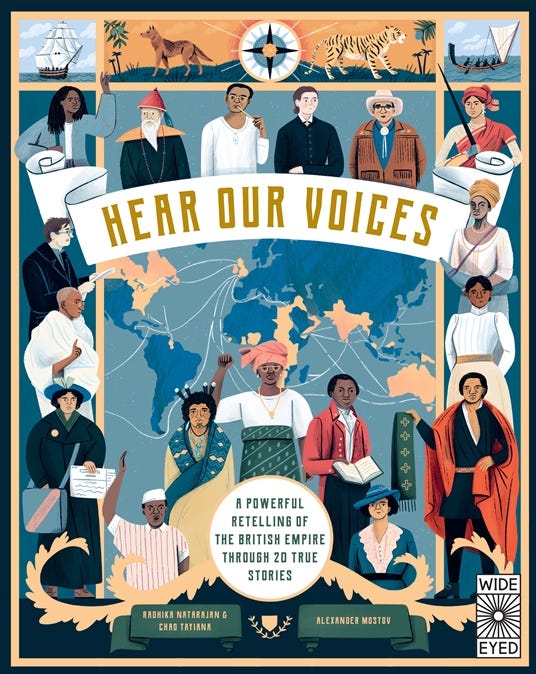

We are so thrilled to welcome our old friend, historian Radhika Natarajan, to the conversation. Radhika released a children’s book Hear Our Voices: A Powerful Retelling of the British Empire Through 20 True Stories, co-authored with Chao Tayiana and illustrated by Alexander Mostov. Albert knows Radhika from their graduate school days; today, she’s a professor of modern British Empire at Reed College, researching migration, citizenship, and the welfare state in the twentieth century. Known for her warmth, generosity, and sharp intelligence, Radhika brings both rigor and humanity to her work—and we’re honored to share this interview with her.

This book is a model of meticulous research, remarkable for the breadth of its geographical and chronological sweep. Beginning in the seventeenth century with Tejonihokarawa, the Mohawk leader who travelled to London, and culminating in the twentieth century with George Manuel, the Indigenous Canadian activist, it spans more than three hundred years…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Broad and Ample Road to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.