On the misery and limbo of waiting places

A guest essay from the extraordinary Zito Madu. Plus, disinformation on Ukraine in Taiwan, Singapore, and China

We’re so honored to share this essay by Zito Madu with you.

We first learned of Zito’s work through one of our interviewees, Nomi Stolzenberg, and have been inspired ever since. What’s striking is his versatility: he can write everything from profiles of professional basketball players to searching personal essays to genre-bending short stories. His oeuvre is varied, surprising, and expansive.

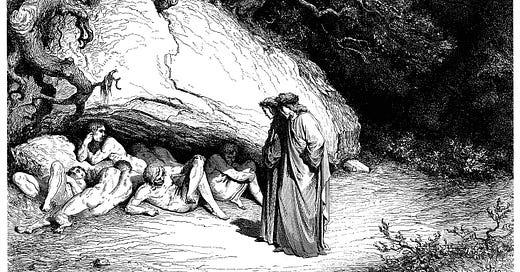

This piece reflects his range. It’s “about” waiting places and poverty but also about Samuel Beckett, the American dream, public spaces, and the dignity of parents who try their hardest to expand our worlds. Zito reflects on the intentional discomfort imposed on the poor. In one passage about the Port Authority, he writes, “Thinking of those people—especially the ones whom police often come in and remove, the ones who aren’t waiting to go anywhere but need a place to rest—I know the misery that surrounds them is engineered.”

If you’re interested in reading Zito’s other work, we loved especially t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Broad and Ample Road to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.