Reading Middlemarch: Coming into Middle Age

Plus, a recap of events in November and book club details

Hello dear readers,

Michelle and Albert here. Sorry we’ve been out of touch—we’ve both had a really nasty bout of illness, and the end of the year in Taiwan is always a whirlwind of events. Plus! We went to Mexico for ten days to attend the FIL in Guadalajara, the biggest Spanish-speaking book fair. We had an amazing time and are still processing everything we learned.

Today, Michelle reflects on revisiting Middlemarch, middle age, and marriage. (So many Ms!) After that, we share notes from our events in Taiwan the past month.

“Tell me, pray,” said Dorothea, with simple earnestness; “then we can consult together. It is wicked to let people think evil of any one falsely, when it can be hindered.”

Lydgate turned, remembering where he was, and saw Dorothea’s face looking up at him with a sweet trustful gravity. The presence of a noble nature, generous in its wishes, ardent in its charity, changes the lights for us: we begin to see things again in their larger, quieter masses, and to believe that we too can be seen and judged in the wholeness of our character. That influence was beginning to act on Lydgate, who had for many days been seeing all life as one who is dragged and struggling amid the throng. He sat down again, and felt that he was recovering his old self in the consciousness that he was with one who believed in it.

For the past year, I’ve been re-reading Middlemarch, a book I’ve read maybe half a dozen times since I first took it up as a first year in college. But this may be the first time that I’ve wept so much while reading it. Sometimes I’m listening to it on audiobook and have to stop walking on a busy Taipei street, to wipe away a tear. Other times, while sitting at my office desk, I sneak a few pages of it on my screen—you can read the whole thing for free on Project Gutenberg—and my eyes get very misty. (“Nothing to see over here, just allergies!” I’ll say.)

Read this book at different crossroads in your life, and you’ll find freshly revelatory lines, new characters who unexpectedly resonate or attract your sympathies. A few months ago, the line that jolted me was spoken by a humbled Dorothea who’s lost all sense of being useful and feels without an outlet to pour her energies. With her incorrigibly honest touch, she says to Will Ladislaw, the man whom she loves, “I used to despise women a little for not shaping their lives more, and doing better things.”

I saw myself in this humbled confession of petty feminine competitiveness. Is self-esteem always built at the expense of others, forged by antagonists to surpass? Is this particularly true for women? Chastened, Dorothea realizes she does not deserve to be so high-minded, and was wrong to believe herself superior to other, allegedly more “conventional” women. For she herself has not lived up to her ideals and has too many days unaccounted for.

Dorothea is much too hard on herself. What she experiences as her singular, devastating failure is in fact the inevitable, bruising realization of middle age: that it is hard it to shape yourself in the way you want, or in the lingo of the younger gen, to “self-realize” and “manifest.” All the more so if you are a person like Dorothea: a heroine with spiritual rather than worldly ambition, who lights up at the idea of helping others, truly wants to do good, and cannot bear the prospect of a life without purpose.

It’s these earnest qualities that make her choice of a partner so disastrous. Propelled by her own independent measures of value, she makes an unconventional choice, unpoisoned by the erotic appeals of money, power, or physical beauty. She believes Mr. Causobon has a superb mind and together they’ll create a body of knowledge.

Her younger sister Celia is comparatively superficial, yet also keenly attuned to Dorothea’s delusions. Her commentary injects the humor that Dorothea lacks about herself:

Celia: How very ugly Mr. Casaubon is!

Dorothea: Celia! He is one of the most distinguished-looking men I ever saw. He is remarkably like the portrait of Locke. He has the same deep eye-sockets.

Celia: Had Locke those two white moles with hairs on them?

An unhappy marriage ensues. Dorothea wishes to help him with his book but begins to question if he has what it takes. Sensing her waning admiration, he withdraws, repelling all attempts at tenderness and shrinking from what he regards as pity.

And then, suddenly, he dies. (Again Celia offers comic relief by being utterly befuddled by Dorothea’s grief: “Dorothea sat by in her widow’s dress, with an expression which rather provoked Celia, as being much too sad; for not only was baby quite well, but really when a husband had been so dull and troublesome while he lived…” )

Eliot is sober but not cynical about Dorothea’s qualities of earnestness and spiritual ambition—traits that also explain her great acts of integrity in public life. If Dorothea’s distinctive character makes her temporarily blind to Causobon’s flaws, then it also disposes her to speak up for Lydgate, a physician wrongfully accused of a crime. They’re not close friends or anything; she defends him on principle, and she does so insistently, unapologetically, and defiantly. All the men, even his friends, urge her to be more “cautious.” (Descriptions calling Dorothea naïve tend to overstate the case; if we decide to call Dorothea naïve, then let’s agree also to call the men spineless.) Indeed, deep moral conviction was the quality that Eliot admired most; her own favorite philosopher, Spinoza, whom she translated from Latin to English, was excommunicated for his views.

And it is Dorothea’s remarkable “naivete” that leads to her second, happier marriage to Ladislaw, a penniless man of “foreign extraction.” (Ladislaw is Polish.) He’s scorned by the propertied and xenophobic snobs in their provincial town. “Oh, he’s a dangerous young sprig,” says one. “Agitator!” decries the Sir James Chettam, who hates Ladislaw. (These little phrases pop up in the Kuo-Wu household now and then.) Ladislaw, for his part, is well-aware of people’s prejudice and discrimination, and he’s got some quips of his own. Provincial towners! he mutters to himself—they’ve never even read Dante, yet they “sneered at his Polish blood and were themselves of a breed very much in need of crossing.”

Causobon has become synonymous with pedantry and incompetence, yet this clueless and sad prig is more human, more sympathetic, more recognizable the older I grow. What ordinary person has not felt what he has—a distrust grown from feeling slighted, a growing doubt in the purpose of one’s own work, an uncertainty about one’s worth? Causobon cannot finish his Key to Mythologies. Deep down he believes he’s a failure, unable to complete the projects that he set himself on. But he’s afraid that if he voices out loud his fears, he will essentially legitimate others’ ridicule. So he stays silent with no friend in whom he can confide. This is the worst sort of loneliness, and Eliot’s empathy for him is acute.

Cruelly, marriage has brought to surface his worst fears. Before, he could hide away in his study, but now he’s daily scrutinized by a partner. Imagine having a brilliant and beautiful fresh bride who adored you when she didn’t really know you and now, up close, thinks you’re a fraud. It must be torture. You might say to poor Causobon: Then you should have let her marry somebody else!

To this Eliot already has a reply: “As if a husband should choose his wife’s husband!”

I laughed hard at that.

When I first read Middlemarch in college, Causobon felt distant in age and experience—perhaps because Celia was always mentioning the hair in his moles. But now, in my forties, I can see he died quite young—in his forties. This has prompted a compassionate turn in the ongoing Kuo-Wu commentary:

Albert: He could still have been great!

Michelle: Yes! He could have finished his book!

Albert: Eliot and Marilynne Robinson started late!

Michelle: So did Toni Morrison!

Could Causobon have been great? Eliot makes it clear that his mind was too muddy. Besides, in a plot point that tickles every Germanist Middlemarch lover I’ve ever met (OK, just one, hi Jim Sheehan!), his book requires knowledge of German, but he can’t read or write a word of it. Gutentag! Or is it Guten Tag?

Virginia Woolf famously said Middlemarch is “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.” No modern review of Middlemarch proceeds without mention of this. Lydgate, who dies at 50 feeling like a failure, is its most tragic instance of adultness. His wife Rosamund has mocked his vocation, drained his expenses, and made daily life a misery. An idealistic doctor who’d dreamed of treating the poor, his lot is to treat the rich. He compares Rosamund to a “plant which flourished wonderfully on a murdered man’s brains.”

But on the flipside, the novel isn’t just about adult disappointment; it’s also about what adult joy feels like, in its muted and attenuated and fragile forms. The feeling, for instance, of being overwhelmed by the goodness of the person you’ve married. This is something that Fred feels, and that I feel, all the time. Or, the feeling of watching someone you love care for someone dying, seeing them grow in these new circumstances. Only a book for grown-ups can explain that the true character of people, including those to whom we make sacred vows, emerges only through the gradual passage of time.

Which isn’t to say that marriage is easy—even happy marriages are hard. Longtime readers of this newsletter will know I’ve written about the grief of becoming a trailing spouse. I’ve shied away from this topic since broaching it years ago, partly out of embarrassment and partly because it’s hard to tell a story when you’re in the middle of it. Hard to believe it, but it’s our fifth year in Taiwan now (!), and as time has gone by, the wrenching choice to give up a certain direction, life force, and ambition in favor of Albert’s desire to come home, has become an incontrovertible given, a foundational condition of daily life. I stumble along each day in a second language, lacking the fluency and self-assurance I once had, grateful for the work that I can get. I’ve joined a lineage I never could have envisioned for myself when I was younger: of wives who give up the satisfactions of self-making to accommodate the dreams of our partners.

Yet my complaint is not the whole story. From another perspective, I have shaped my life, and for the better: I chose this collective, I chose this union, I chose the new perspective it offers, and yes, I chose the uncertainty of an intertwined life. Eliot understood these contradictory truths of love and pain, depicting them with such poignancy; this, more than anything else, is what has been making me cry.

“Married life is wonderful; marriage can suck,” I texted a friend recently. The balm of companionship; the curse of having to exist as a single unit. Albert, with his blessed lack of defensiveness, knows exactly what I mean. (Or perhaps he feels the same way, too; he has to live with my parents for half the year when they come to Taipei.) When, recently, I’ve seen symptoms in him that I’d never seen before, fatigue and exhaustion—he’s usually so energetic and cheerful—my catastrophic imagination, as usual, leapt to the worse, and I imagined I’d somehow given him a terminal illness.

“Am I slowly killing you?” I asked.

“Maybe we’re slowly killing each other,” he replied, and then we laughed.

The disappointments of middle age are real, bruising, and significant enough to be wrestled with in the highest literature, and Eliot has her own prescriptions for what makes life survivable. Paradoxically, she seems to say, an acute sensitivity to the world does not kill us but saves us, attaching us to the very life that we may seek to be rid of. Her justly famous line communicates a moral world: “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.” Influenced by Spinoza, she believed in the interconnectedness of our lives and the notion that God exists everywhere. If we let ourselves hear the “cry from soul to soul”—those fitfully illuminated flashes of need, thirst, and emotion—we may be born again. Not in the evangelical Christian sense, which she rejected to her family’s anger, but in the belief that joy comes from mutual need and our capacity to fuse our inner lives to the thread of the universe.

When I was young, I identified with Dorothea; later, as I struggled to write, I felt (and still sometimes feel) like Causobon. (And so did Eliot herself: “I am in a certain sense Casaubon,” she wrote in her diary.) Now, to my surprise, I joke that I’m Fred. Fred was an idiot wastrel and does not deserve Mary, but he gets her anyways. And he tries heartily to live up to this windfall. But his redemptive quality is that he knows what a windfall she is.

The first time I read it, at 17, the professor Leo Damrosch told us that he preferred teaching this book to his extension school students. They were older and had gone through more. Reading the book, they all ended up weeping together. Young people, he said, simply didn’t understand it the same way. Of course we freshmen simply did not register this comment. We could not even conceptualize the forms of knowledge that lay beyond our grasp. But now I think often about it. This is a book that means so much to so many people. For me it has meant everything.

A Few Notes From Taipei

Michelle moderated a conversation between two inspiring & lifelong advocates of abolishing the death penalty: Carol Steiker of Harvard Law School and Chuanfen Chang, chairperson of the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty (TAEDP). Last year, the constitutional court in Taiwan declined to end the death penalty. Our soul-searching conversation came at a time when morale about the prospect of abolition is very low; last year our constitutional court declined to abolish it. We talked about how to broaden our dialogue, shifting our focus to human dignity and the limits on the power of the state to kill. Thank you to everyone who came out on a rainy night.

New Bloom organized a terrific panel discussion that introduced Taiwanese comics and children’s books. Among the delightful bits: the challenges and creativity required to translate multilingual Taiwan; the comparison of Japanese time traveling mechanisms to Western ones, and the vividness of onomatopoeia. Thanks to Brian Hioe, Elizabeth Hsinyin Lee, and Michael Fahey for the great conversation.

Over at Amnesty International, we had an intimate if a little painful conversation about Reading with Patrick, a book that I published what seems like so long ago—and yet the question of how to live without hypocrisy in a world of inequality is even more pressing and daunting now. I read aloud from parts of an old Substack and questioned whether there’s any point to publishing, whether it’s driven mainly by ugly ego and ambition. The following day, feeling a little unconfident, I asked a student-friend if I’d been too much of a downer. He said, “Nah, it was refreshing; most writers are like, ‘My book is great and I’m great.’” Thanks Gabriel for that! And many dear thanks to Naomi Goddard and EJ at Amnesty International for organizing this conversation with such deep care and thoughtfulness.

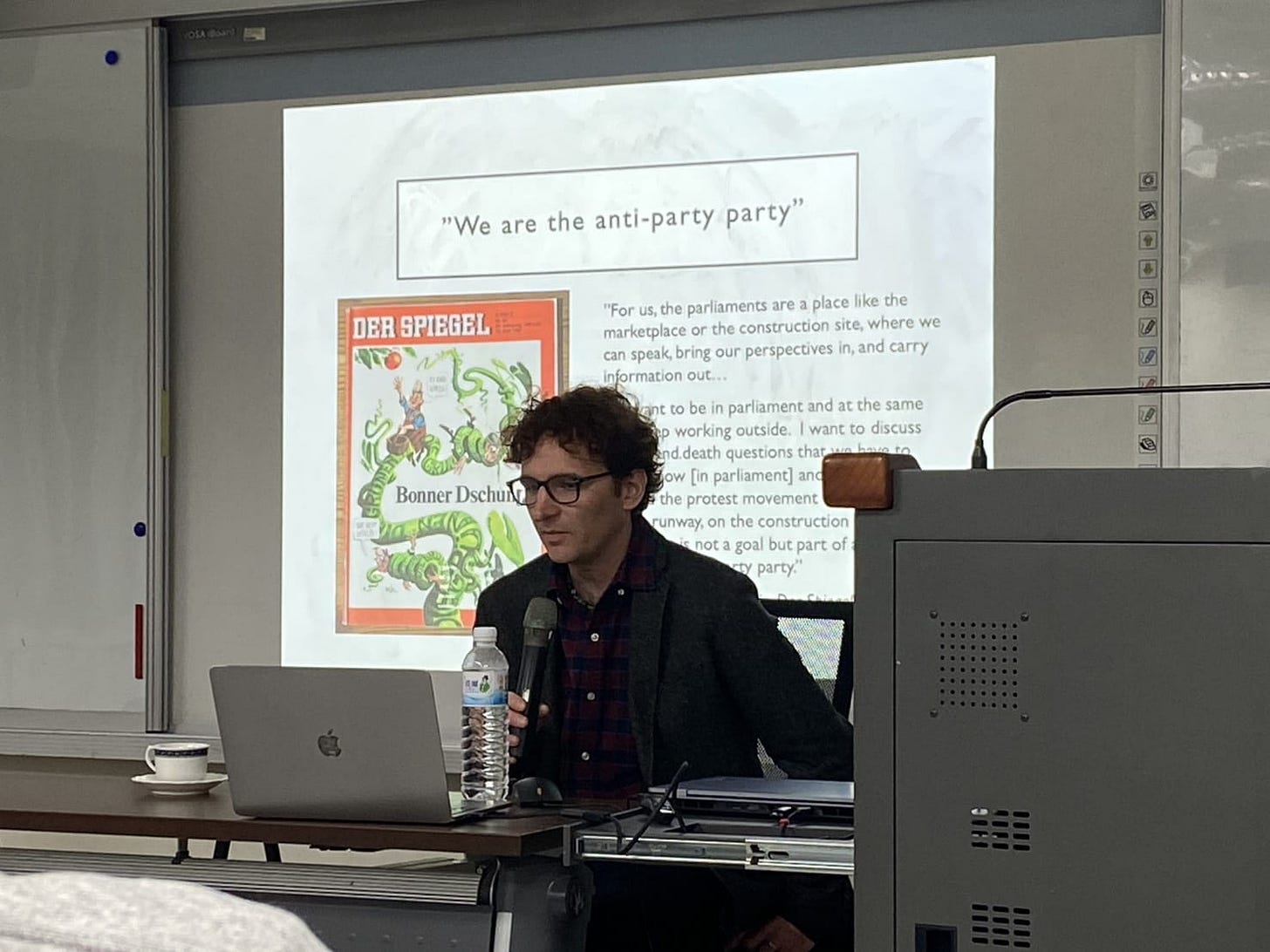

Stephen Milder, a scholar of environmental history in Germany, visited Taiwan and gave two lectures sponsored by Academia Sinica. The first explored the myth of green Germany and the other was on Petra Kelly, one of the founding members of the Green Party in Germany. Students were totally immersed in his stories of Petra Kelly, who traveled the world and got “arrested everywhere she went.” In South Africa— she was a sitting legislator at the time!—she occupied the German embassy to protest apartheid.

Albert organized a screening of the film Island of the Winds, a Taiwanese documentary film about an anti-relocation movement of the people at Losheng Sanitorium, a leper colony. The film contains moving scenes of the elderly people there, many of whom were placed at the sanitorium as children, separated from their families. We were struck by the director’s remark that she’d studied leper colonies all across in the world, but here in Taiwan they have perhaps the strongest sense of identity, self-worth, and belief that their home must be preserved. They’d wake up at 3 AM to get ready for a protest to fight relocation and demolition. “Only until I met the people here,” she said, “did I understand what they mean by ‘Fight to the last breath.’”

And the music and the songs they’d sing! This one:

Enduring a miserable life

I’ve regarded the sanatorium as home for 60 years

The heartless government prioritizes profits

and sells out the patients of Losheng

And last, our six-year-old’s preschool went on an excursion to a sweet potato farm near Jin Mountain. They planted sweet potato leaves and roasted sweet potatoes:

Some Links

The North American Taiwan Studies Association 2026 conference is scheduled to take place on June 26–28 at Indiana University Bloomington, co-hosted with the Taiwan Studies Initiative at IU. This year’s theme is “Resonance/Dissonance — Taiwan Studies, Knowledge Production, and Power Asymmetry,” with a particular focus on the histories and infrastructures involved in building and sustaining Taiwan Studies as a discipline. There are two essay competitions this year—one for undergraduate students and another for graduate students and emerging scholars (co-hosted with The International Journal of Taiwan Studies).

Here’s the CFP for NATSA 2026, the link to the Undergraduate Paper Competition, and here’s the Graduate and Emerging Scholars Essay Award. Thanks to I-Lin Liu, president of NATSA, for sending along the info!

Shout-out to The Taipei Edit, a new newsletter that curates exciting things going on around Taipei. They’re doing a great job finding terrific cultural events going on around town.

Book Club

On January 9th / 10th (Friday 7 PM EST, Saturday 8 AM Taiwan time), we’ll read Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington. On March 6th / 7th (Friday 7 PM EST, Saturday 8 AM Taiwan time), we’ll read Percival Everett’s James. Thanks to our book club members for their suggestions! Please reply to this email for a zoom link.