Underdog Stories in the Shadow of Empires

Two Taiwanese Graphic Novels about Memory and History

Dear all,

Michelle and Albert here. For this week we’re recommending two dazzling Taiwanese graphic novels.

One of the most distinctive features of Taiwanese graphic novels, comics, and children’s books is their sustained engagement with history. Taiwan is special in this way. Its storytellers are deeply interested in recovering, reworking, and rethinking the past. This has much to do with more than four decades of martial law, when stories were circulated underground, told in hushed tones. The years leading up to the lifting of martial law in 1987 were turbulent and hard-fought, and the victories unleashed a drive to tell one’s own story—along with a sharp awareness of how precious this freedom is.

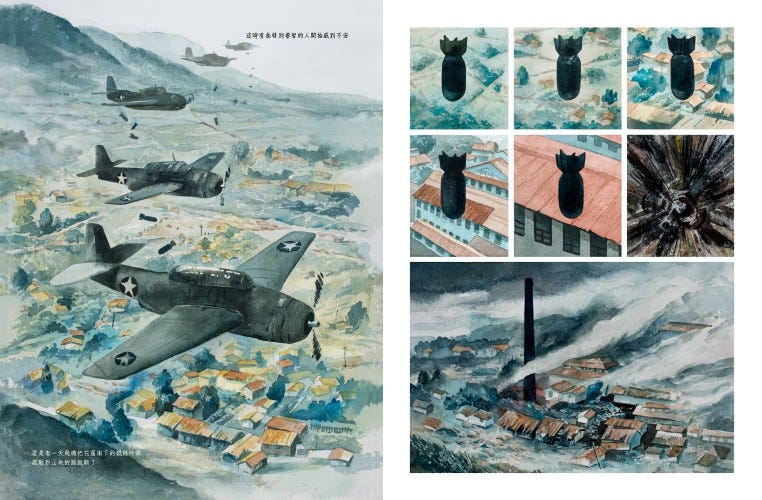

The two books we want to highlight today wrestle with the long shadow of Japanese colonization. Both open with the image of American planes dropping bombs—an indelible memory for many Taiwanese of that generation. Both grapple with the shift from Japanese rule to the Kuomintang (KMT). Both seek to capture on the page the multilingual soil of Taiwan, switching between Mandarin, Taiwanese, Japanese, and other languages. One centers on a household name, the poet Yang Mu (pen name of Wang Ching-hsien 王靖獻), whose Japanese name was Oken. The other follows Tân Chhoàn-tē, who fought a five-year guerrilla war against the KMT government but remains barely known outside specialist circles. Both of these books show how individual lives were deeply shaped and formed by the currents of twentieth-century global and imperial history.

For the past year, we’ve been deep in Books from Taiwan 2.0, a long-term initiative of Taiwan’s government. (I say “we” because I’ve dragged Albert into it, haha.) You can find the full catalogue online; my team manages children’s books, manga, and graphic novels. (Check out our IG devoted to these books, too!) We commission and manage Chinese-to-English translations of these books, circulating them among foreign publishers. English is the lingua franca—whether the publisher is German or Korean or Turkish, the first question is always: Do you have an English PDF? Still, many of these translations will never reach an Anglo reader, because it’s hard to get Anglo publishers to buy Taiwanese books.

Meanwhile, loads of crappy American books get exported to foreign countries, but American publishers rarely buy foreign titles. As I mentioned last fall, less than one percent of children’s books are translated, and the numbers are only slightly better for fiction. This is insane and explains partially why Americans are, as a whole, more ignorant about the world than other peoples.

A bit about the job: maybe we’re naive, but there’s still some whiplash seeing the way people “in the industry” talk about books. It seems self-evident that what sells is a different category from—and sometimes even antithetical to—what’s good. When those categories happen to converge, this is a happy and rare thing. Good readers will champion books that don’t appear sellable to mainstream audiences. Maybe they’re books that are “difficult” because they demand complexity, ambiguity, discomfort, or readerly self-interrogation. Maybe their ideas, characters, styles, or forms are ahead of their time. And—just maybe—it’s because the books come from a country nobody has ever heard of (like Taiwan, for instance!..)

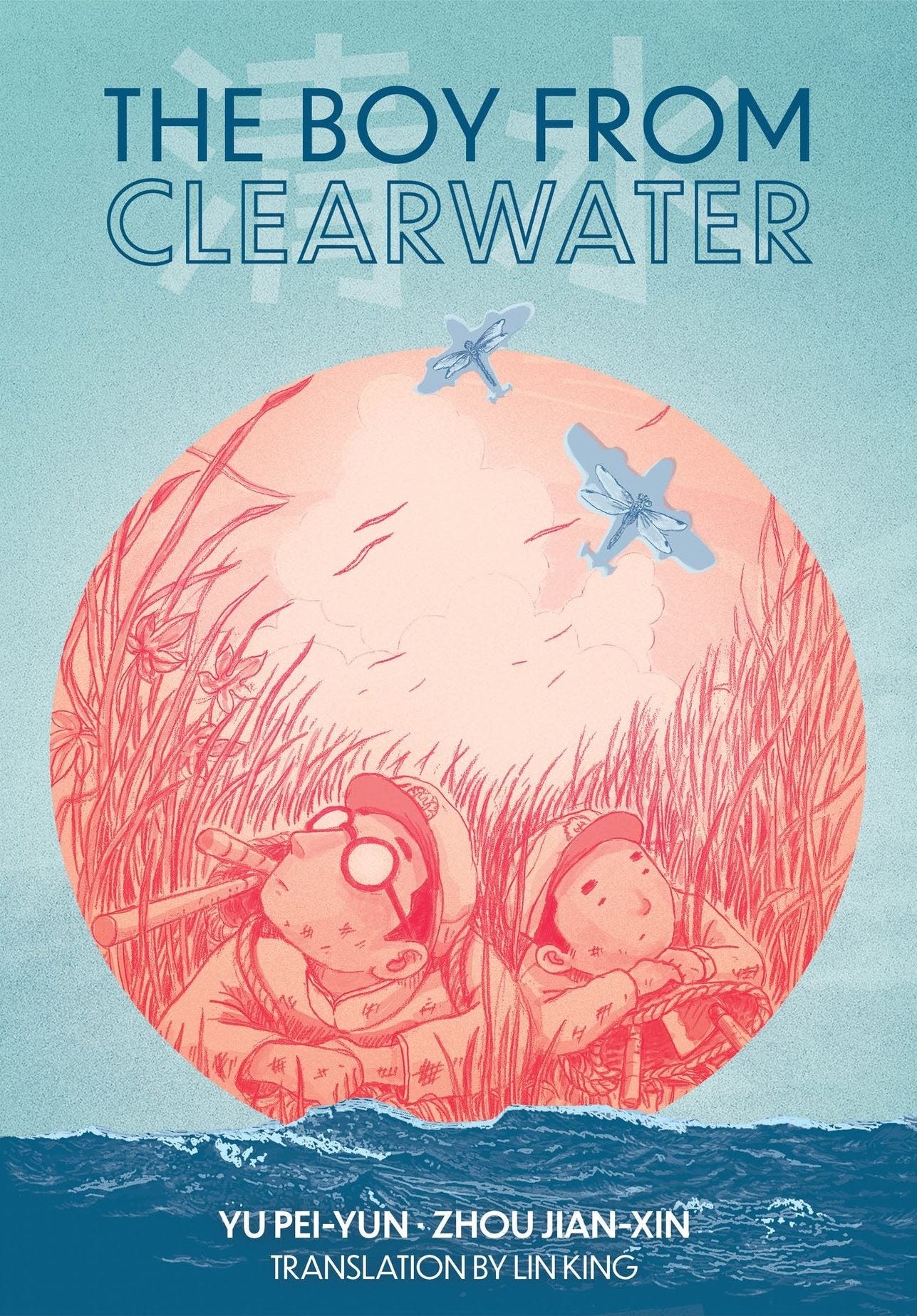

Books dealing with Taiwanese history will have to be extraordinary for any international publisher to even consider it. In the American industry, as far as I know, there’s only been one publisher that has released a Taiwanese graphic novel on Taiwanese history: God bless Levine Querido, the indie publisher that brought Boy from Clearwater to English readers. It’s written by Yu Pei-Yun, who teaches at National Taitung University, and illustrated by Zhou Jian-xin, a celebrated artist in Taiwan. The wonderful translation is by the acclaimed Lin King. Boy from Clearwater is my go-to gift for younger readers who are curious about Taiwan. (I’ve also gifted it to adults, and yes, I’m suggesting it now as a stocking stuffer for Anglo readers!) This is a beautiful, harrowing, and ultimately hopeful story of Tsai Kun-lin (see video interview below), a man who spent 10 years on Green Island, a prison for dissidents, after attending a reading group. In his last years he became a volunteer at the human rights museum, sharing his story with visitors. As we mentioned previously in a newsletter on transitional justice, we met a lovely 24-year-old whose most cherished memory was meeting Tsai a few years before Tsai passed away. As he told us, Tsai’s eyes, even at age ninety, still burned bright.

Albert and I have always rooted for the underdog. We like underdog causes, underdog countries, underdog scholars, underdog publishers, underdog writers. Within the international market, Taiwanese books are the underdog. That's why you don’t see Americans publishing many Taiwanese books (or books from any countries, to be fair). That's starting to change, thanks to the good work of the Taiwanese government in investing in its writers, translators, and artists, and to the Taiwanese agents and publishers who have nurtured local storytellers. (And to be sure, this isn’t to make Taiwan sound like a faultless actor in the market; I think it should be translating more books from Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia instead of giving Europe and the U.S. such attention.)

The two books we’re featuring today aren’t available in English—and that’s exactly why we’re featuring them. (We do have two beautiful English translations, but they’re the property of the Taiwanese government, so they can only be circulated to interested publishers.) But, we met two adorable book lovers at a picnic yesterday who suggested that we should crowdfund and start a publishing house. Honestly? That would be amazing! Let us know if you’d like to join us in a very underdog endeavor.

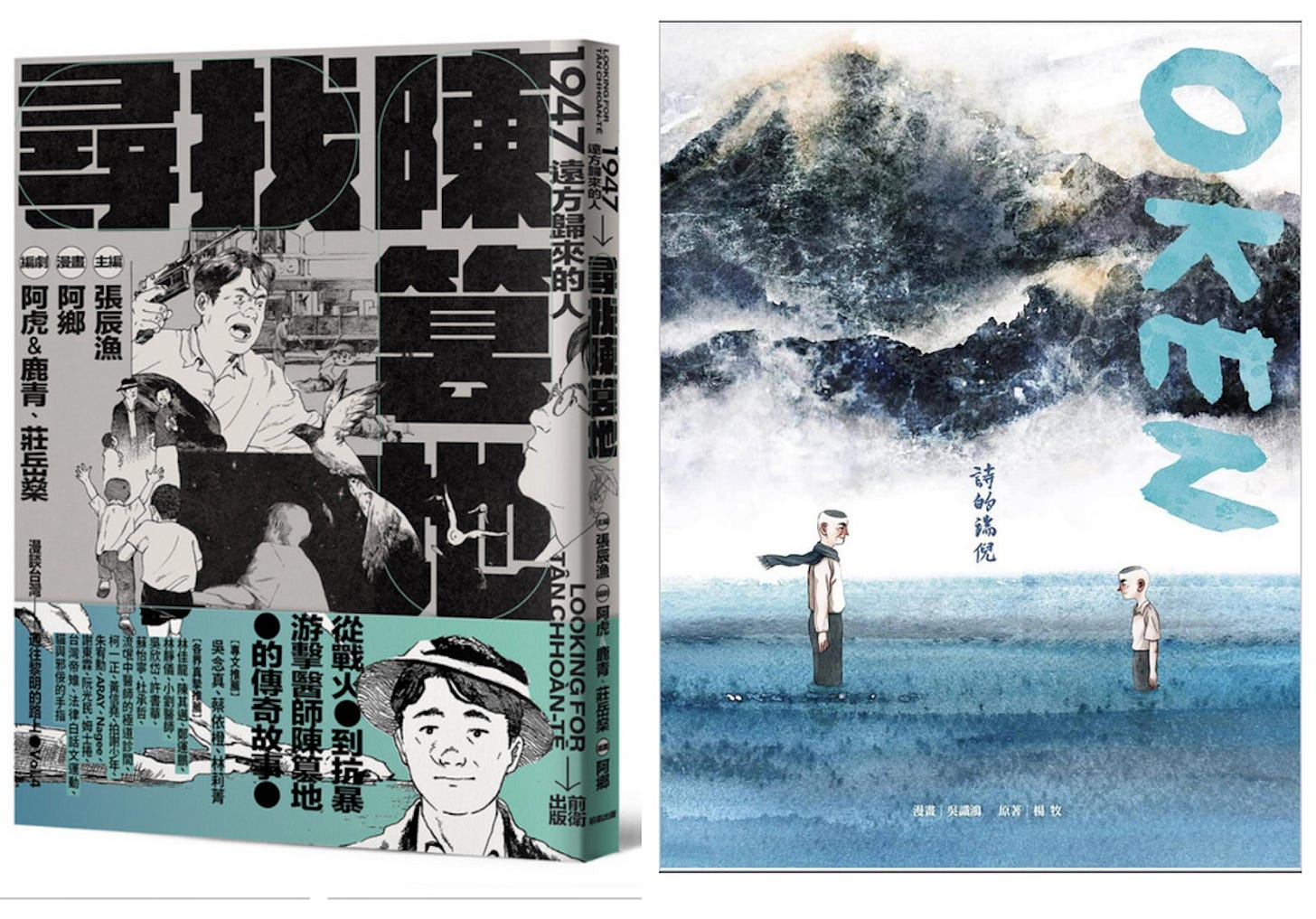

OKEN: Childhood Memories of a Taiwanese Poet 《OKEN:詩的端倪》

This graphic novel is a gorgeous book, a consummate work of art. It adapts classic Yang’s Mountain Wind, Sea Rain (《山風海雨》), transforming this collection of literary essays into a Bildungsroman by one of the important Taiwanese writers of the twentieth century.

Wu Shih-hung (吳識鴻) has a background in illustration and animation. His style is hard to pin down; sometimes his drawings have the calm simplicity of classical Chinese painting, sometimes the bold energy of manga, sometimes the raw, fleshy intensity of Lucian Freud’s paintings, and sometimes the dark, emotional weight of Käthe Kollwitz’s woodcuts. Here is an example of Wu’s work before Oken.

This may seem overwhelming, but threaded through Yang’s life, it works. And the result is simply stunning to look at, a visual achievement that matches the depth of its subject.

Michael Fahey, who has lived in Taiwan since the lifting of martial law, translated Oken for Books from Taiwan. As he notes, “Although Yang Mu was an erudite scholar as well as a poet, we do not see him reading. Instead, we learn that Yang’s artistic model is a Taiwanese temple craftsman, fiercely dedicated to carving gods from Taiwan’s precious cypress wood. This fusion of nature, art, and healing lies at the heart of Yang Mu’s poetics.”

The book moves effortlessly between moments of intimate artistic creation and broader social horror. Yang’s young life was shaped by a series of dramatic disruptions—bombings, earthquakes, political regime change.

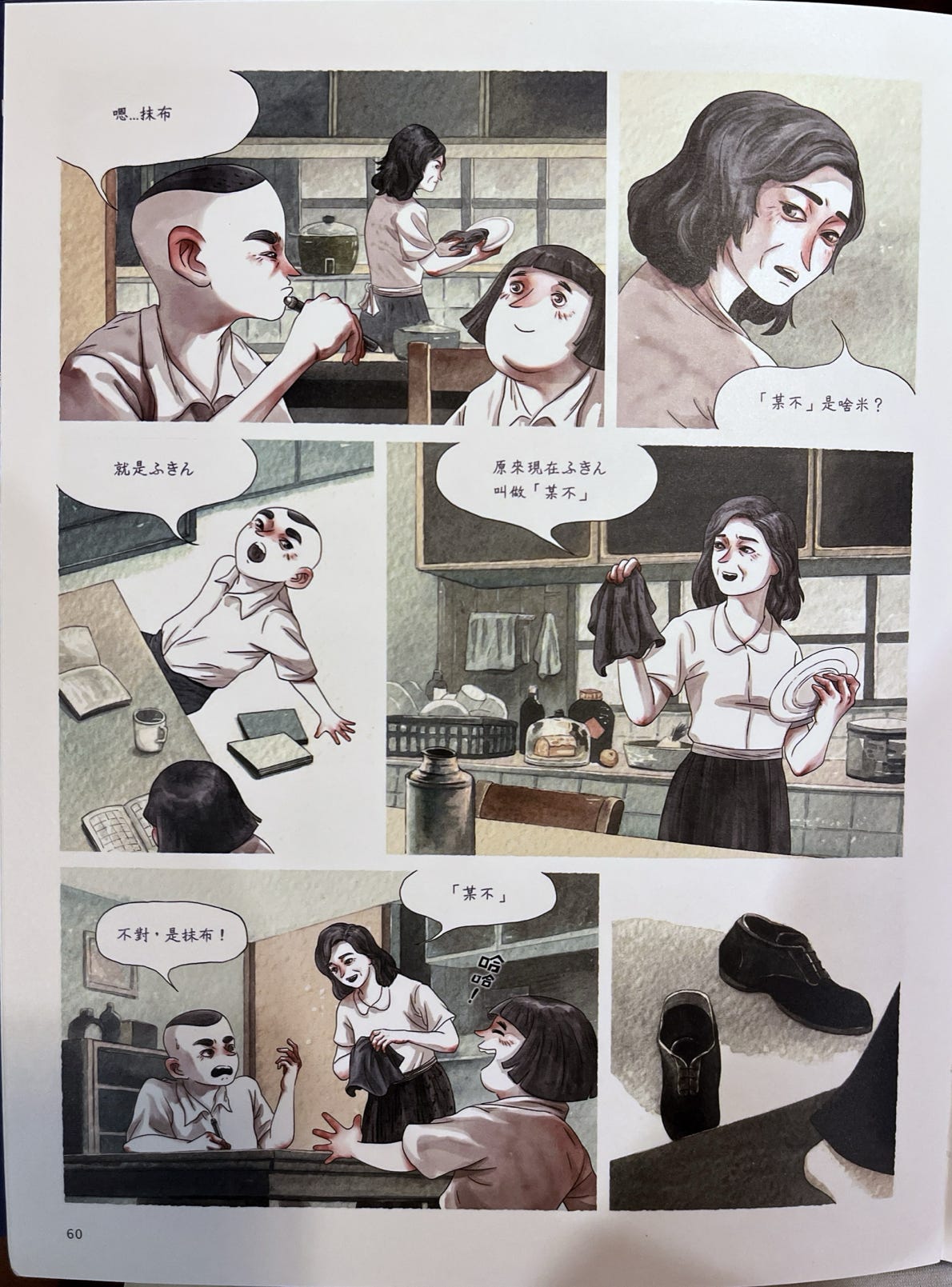

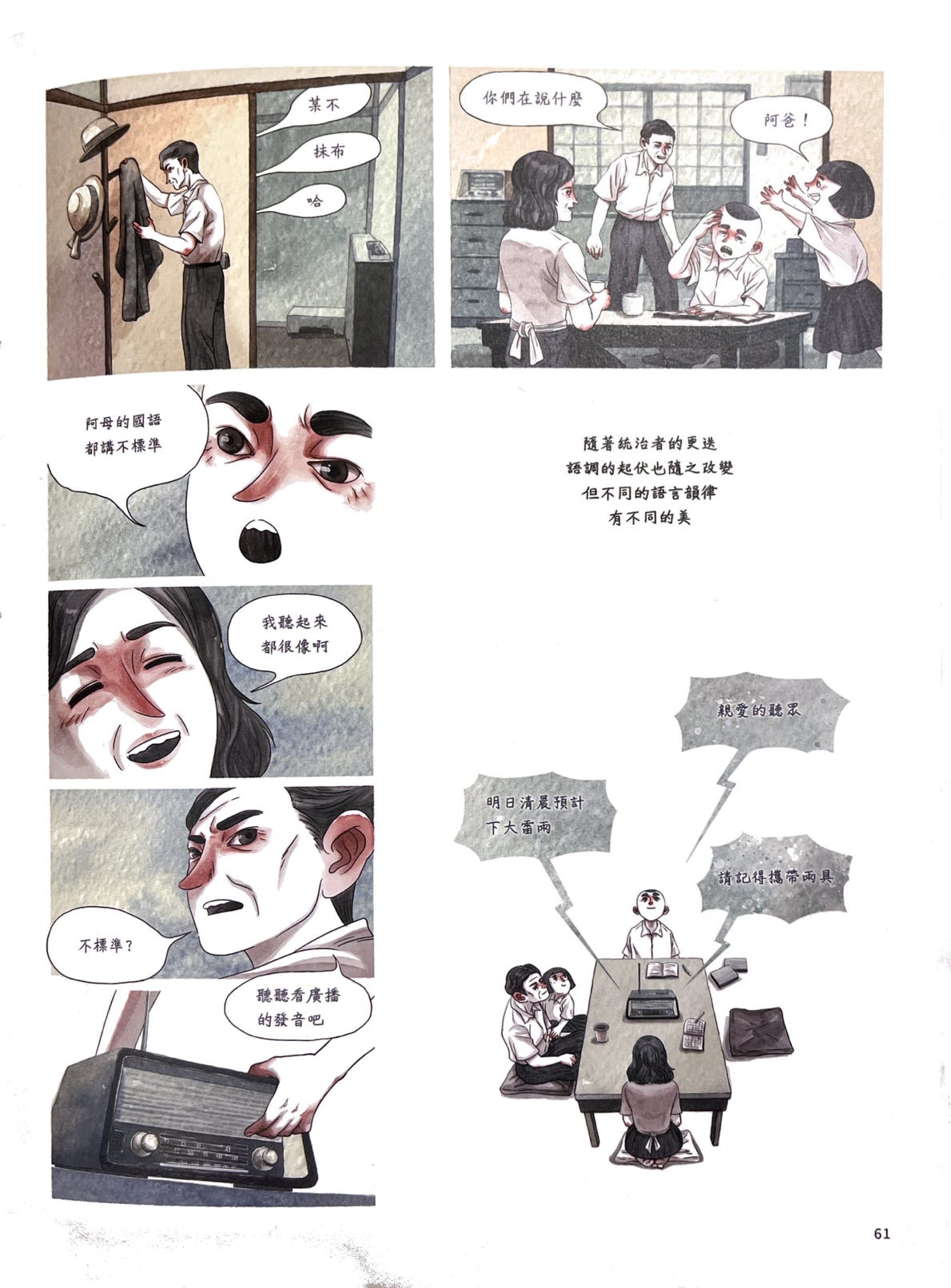

Like Boy from Clearwater, one of the book’s most striking features is the way Oken navigates Taiwan’s complex multilingual terrain. Hualien, where Albert’s family is from, was a particularly fertile ground for such encounters, and the narrative moves fluidly between Taiwanese, Japanese, indigenous languages, Mandarin, and English.

A memorable spread captures a humorous yet poignant moment just after the KMT has taken over Taiwan. A young Yang is struggling to learn Mandarin. His mother, who speaks only Japanese and Taiwanese, overhears him practicing. She tries to pronounce the word that he’s learning—“rag.” Then, he begins to correct her pronunciation. Ultimately, both mother and son learn the “proper” sounds from the radio. Though there are tragic scenes in the book, Yang imbues this scene with tenderness and humor. “Our rulers had changed,” writes Yang Mu. “Yet the cadences of Japanese and Mandarin each had their own beauty.”

Particularly striking is the way Wu captures the mysterious and dramatic landscape of eastern Taiwan, particularly this spread of Qilai mountain in Hualien.

In 1966, Yang left Taiwan for the United States, where he would spend the next three decades. At book’s end, the book lightly touches on the melancholia of the diaspora. We’ll turn over to Fahey here, who captures the ending better than we can:

The novel ends with our narrator in Seattle, three decades later. Taiwan has just emerged from the darkness of state terror and democratized. He is heading to a literary event with his son. His books, in English, are on display in the window of the shop. He shares his values with his son: freedom, artistic expression, and the beauty of nature. Yet we sense that the story he has told—of trauma, a specific time and place at the western edge of the Pacific—is a story that only he can tell. There is a gulf between an immigrant father and his son, born into a new world. And yet, in the novel’s final image, the famous poet looks at his son and sees not the child of a new world, but Oken—the boy he once was.

*

It’s not available in English, unfortunately, unless you count Fahey’s translation, which is terrific but only available to interested publishers. But if you read French, you can buy it here; and German, too. (Thank you French and Germans for caring enough to buy Taiwanese works and recognizing quality!) You can find two different samples of the book in English, here and here. It’s published by Fisfisa, and you can buy the Taiwanese edition here.

Looking for Tân Chhoàn-tē: 1947, The Man Who Returned from Afar 《尋找陳簒地:1947遠方歸來的人》

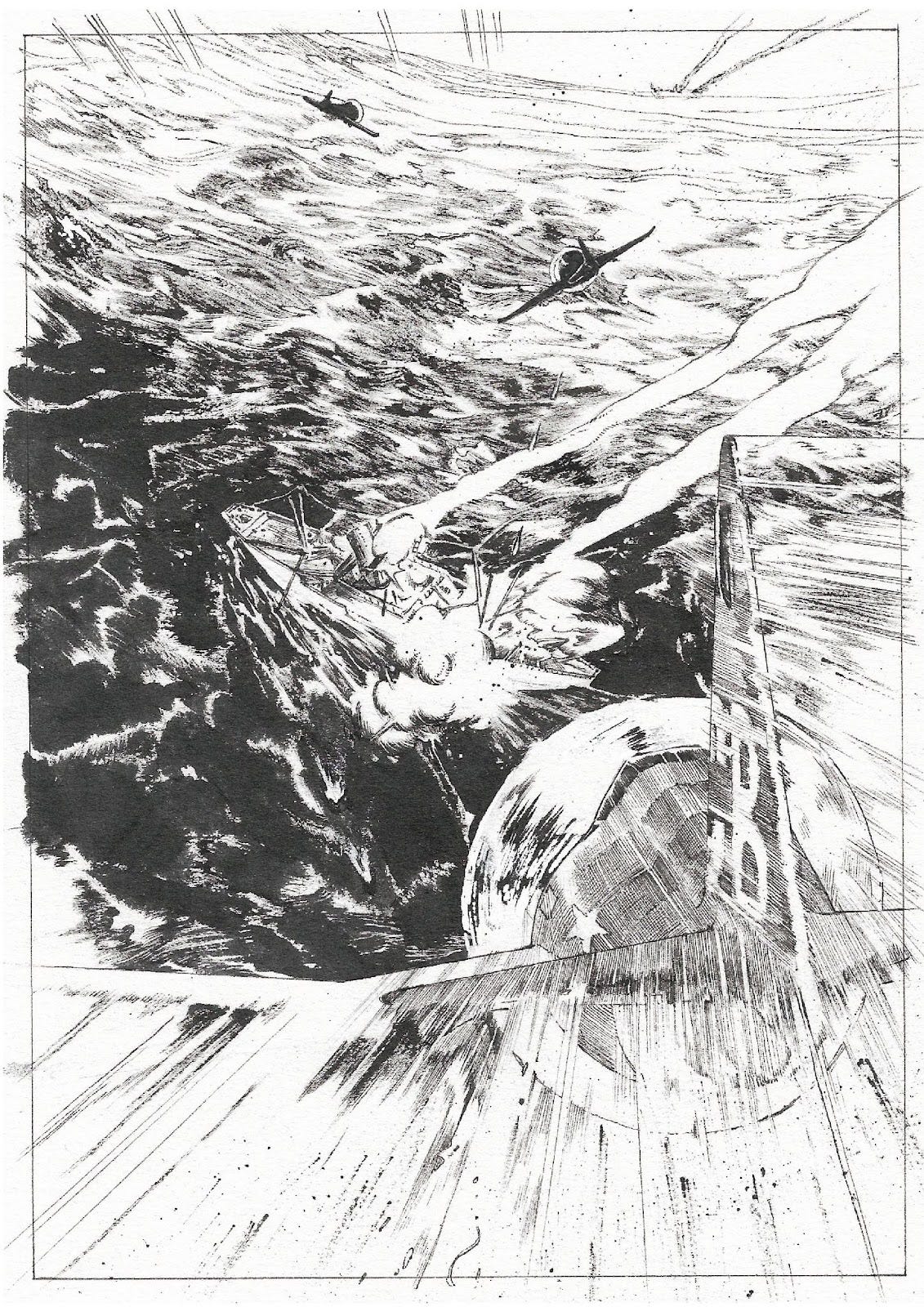

Like OKEN, this book kicks off with a dramatic scene: it drops us into the cockpit of a fighter jet, swooping down to attack a ship off of the coast of French colonial Cochinchina. On the page, we see bombs rain down on it.

We soon learn that the ship attacked is the Shinshu Maru, a vessel considered somewhat legendary among aficionados of military history, as it was the first purpose-built amphibious assault ship designed to transport landing craft and hangars.

The attack sunk the ship, and 339 people died, most of them farmers. Only 95 people survived.

Among the survivors was Tân Chhoàn-tē (陳簒地 1907-1986), a medic on board. He is not a household name to Taiwanese of our generation. As the director Wu Nien-chen writes in his preface to the book, he is one of the “countless lives of common, everyday people” (tr. David Knight) who lived through the dramatic events of the twentieth century. In 2018, a group of young creatives stumbled across the story of Tân. Something about his life grabbed their attention, and they launched a project meant to piece together the details of his life. The result is this book: “Searching for Tân Chhoàn-tē.” It’s published by Avanguard, a publisher we admire for its integrity, vision, and commitment to public history. (We’ve previously written about Avanguard’s book Democracy on Fire.) It’s written by Chen-Yu Chang, Che-Yu Kuo, Yueh-Shen Chuang, and illustrated by A-Hsiang.

Tân grew up steeped in a Han Chinese identity, his childhood shaped by his family’s fierce anti-Japanese sentiment. Like many promising students of his generation, he went off to study medicine at Osaka Medical College. There, he fell in with Japanese leftists, and he joined a group of underground Japanese communists. In 1933, Tân was arrested and spent two years in prison. A Japanese professor eventually bailed him out, and he was able to finish his medical degree.

Back in Taiwan, he set up a medical practice in Douliu, Yunlin. He married and had children. But the escalating World War caught up with him. In 1944, he was drafted as an army doctor, shipped off to Southeast Asia, where he survived the attack on the Shinshu Maru. He was then deployed as an Army doctor to Japanese-occupied Vietnam. There, he brushed shoulders with Hồ Chí Minh’s Việt Minh guerrillas—picking up lessons in guerrilla warfare that would later be instrumental.

In April 1946, Tân returned to Taiwan. Within a year, the island erupted in the February 28 Incident. Tân became a local leader. He rallied militias in Dou-liu, fought back against Nationalist troops, and then joined forces with Zhang Zhi-zhong’s so-called “Democratic Allied Army” in Chiayi. The effort collapsed, and Tân retreated into the mountains, waging guerrilla war until May 1947.

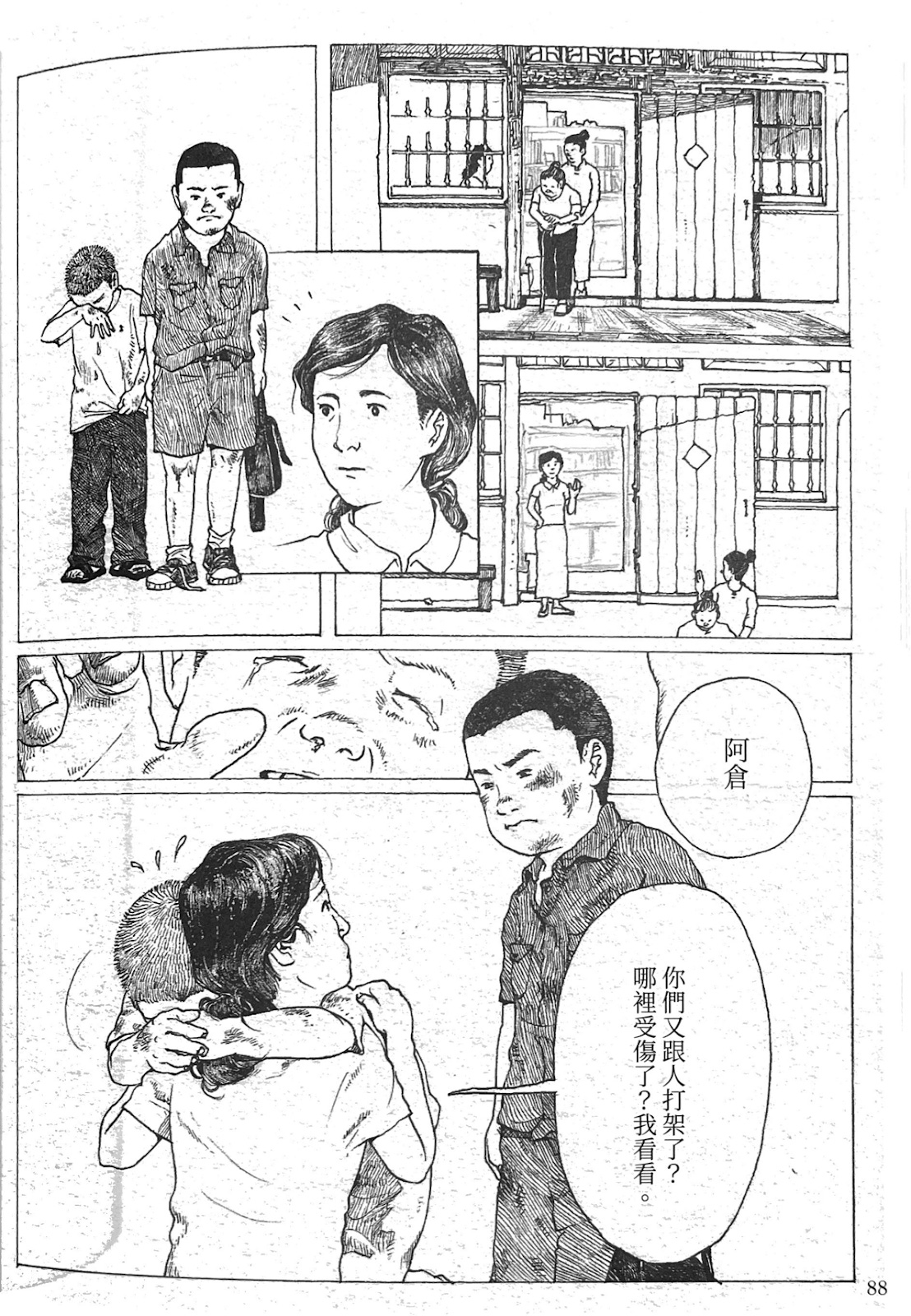

Defeat pushed him underground. He lived in a cave in the hillside for five years. One of the most heartbreaking parts of the book shows how this guerrilla life left its mark on his children. Other kids ganged up on them and mocked them: “Oh boy, you’re lucky. That’s one lucky fugitive.” Or they sneered: “Burrowing rat! Ah-tsang’s Dad is a burrowing rat!” Parents told their kids to stay away: “My dad says your old man is an outlaw who did wicked stuff. So now he’s gonna hide out. She says I can’t play with you.” The children begin to doubt their father’s innocence, turning to their mother, saying, “They… they… they all say Dad is a bad man.”

Only in May 1952 did he surface, surrendering to the KMT. The regime paraded him as a “reformed communist” in propaganda, then cut him loose in 1953.

The guerrilla became a doctor again. Tân opened a modest clinic near Taipei’s Jiancheng Circle, tending patients quietly, far from the battles and barricades that had once defined him. By the time he died in 1986, he had lived both lives: insurgent and healer, revolutionary and physician.

For us, coming across stories like Tân’s is a reminder: Taiwan has always had a complicated revolutionary history, one that was never just local but deeply transnational—running through the Japanese empire, across Southeast Asia, entangled with movements like the Việt Minh. It’s a history that was stamped out, buried under martial law and decades of silence. Recovering Tân Chhoàn-tē’s life means recovering that suppressed tradition, and recognizing that Taiwan’s past is full of unfinished revolutions.

All above translations are from David Knight, who writes, “I can imagine a Taiwanese reader turning to this book and finding compelling confirmation of the familiar; I imagine a foreign reader finding inspiration in realizing the magnitude of Taiwan's victory as a thriving democracy.” You can buy a copy of the Taiwanese edition here.

Some Links

We think social media is a death machine, but that said, Michelle has been managing an instagram account with her team at Books from Taiwan, where we post one children’s book and one manga or graphic novel daily, and you can also find Michelle here and Albert here.

Read Fahey’s essay on Oken in full here.

If you want to dive deeper into this revolutionary past, check out Catherine Lila Chou and Mark Harrison’s wonderful Revolutionary Taiwan. There’s a particularly great chapter on how the moniker “Chinese Taipei” came to be, but the whole book is great. On diasporic activism in the United States, see Wendy Cheng’s Island X; we saw her speak at a fantastic event at New Bloom.

Check out Wayne Wong’s essay on Jeffrey Wasserstrom’s new edition of Vigil. A good quote from it: “Wasserstrom wrote not as a distant scholar but as a Western observer aligned with local voices, attentive to the affective textures of protest. Yet he maintained a studied humility, frequently deferring to local journalists and cultural producers.”

Kerim Friedman wrote an excellent piece on Taiwan and Gaza. As Friedman writes, “Taiwan’s Cold War legacy still haunts its international relations, leaving it unable or unwilling to speak out against the genocide in Gaza, even as it offers support to Ukraine against Russia.”

In case you are like us and didn’t know much about Charlie Kirk, we recommend the most recent “Panic World” podcast. These podcasters have been following Internet culture for 15 years and helpfully illuminated the context surrounding Kirk’s assassination. The takeaway: social media is a radicalization engine that has ushered in a new era of sectarian violence.

Book Club

We loved talking to you all about Patricia Engel’s Veins of the Ocean! Our next book club is Friday, October 24th 7 PM EST / Saturday, October 25th 7 AM Taiwan time. We’re going to read Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo for the October book club. After, we’ll be reading Miranda July’s All Fours, Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Percival Everett’s James, and Natalia Ginzburg’s Road to the City. The book club is open to all paying subscribers. Thanks to our book club members for their suggestions! Please reply to this email for a zoom link.

And last, an eco-friendly chicken farm in Beitou. The chickens do seem happy here! We learned that chickens are not indigenous to Taiwan and that they bathe by rolling around in the dirt. Here’s our daughter with the chickens:

Yes! You should crowdfund and start a publishing house!

Thanks for the book recommendation! I just put The Boy From Clearwater on hold at the library :) Also looking at your list of upcoming books for the book club, I'd recommend sneaking in the graphic novel Big Jim and the White Boy: An American Classic Reimagined by David F. Walker. It's a really fast read and I thought it was so compelling. It would be great to compare to James. (I still need to read James by Percival Everett, but did read several of his wife, Danzy Senna's books this winter.)