Was the atomic bomb a war crime?

For the first time, Albert’s students overwhelmingly think so. Plus reader responses, links, book club info, & bonus audio from baby P.

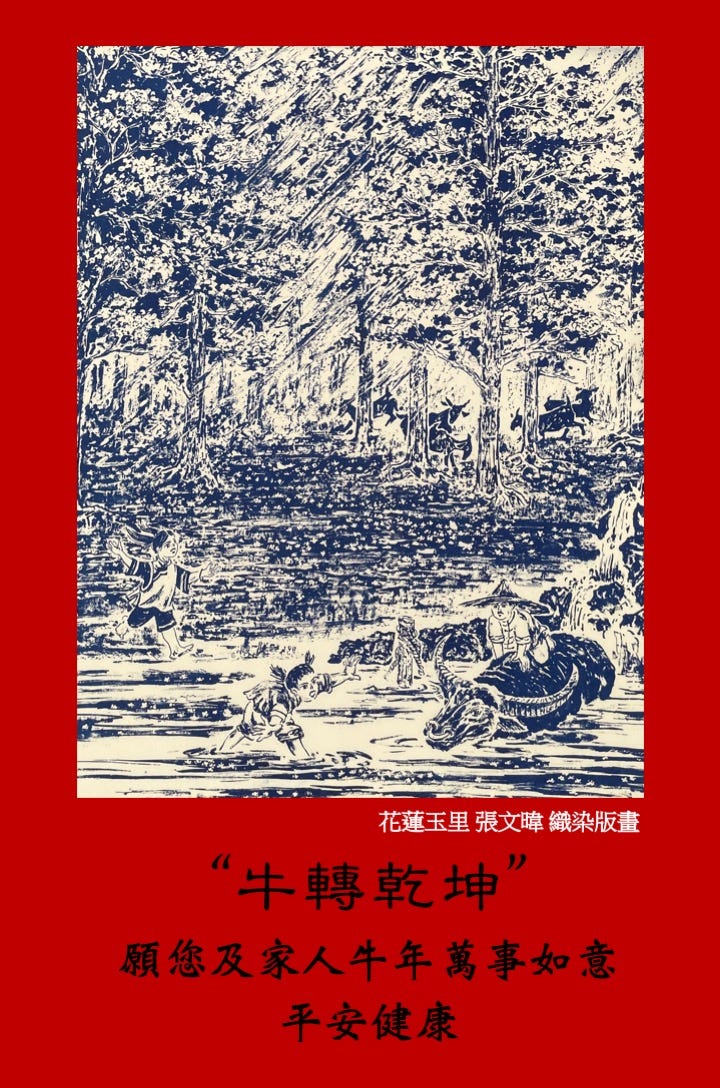

Happy Lunar New Year, friends! Goodbye Rat, Hello Ox!

Making your own new year's greeting card is all the rage in Taiwan. Here’s what Albert’s dad made:

Albert on teaching the atomic bomb and the sea-change in his classroom:

First, a graph. (I typed the question hastily into an online polling app; it should really read “Do you think the use of atomic bombs in World War II was a war crime?”)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Broad and Ample Road to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.