Comical family psychodrama at the Taipei International Book Fair

Plus, a new edition of Michelle’s book in Taiwan, and supporting Palestine

Hello readers,

Today is the last day of the Taipei International Book Exhibition. If you’re in Taipei, you can still catch some of the chaotic fun — the book fair goes until 6 PM! Although be warned: if today is anything like yesterday, the crowds will be pretty intense.

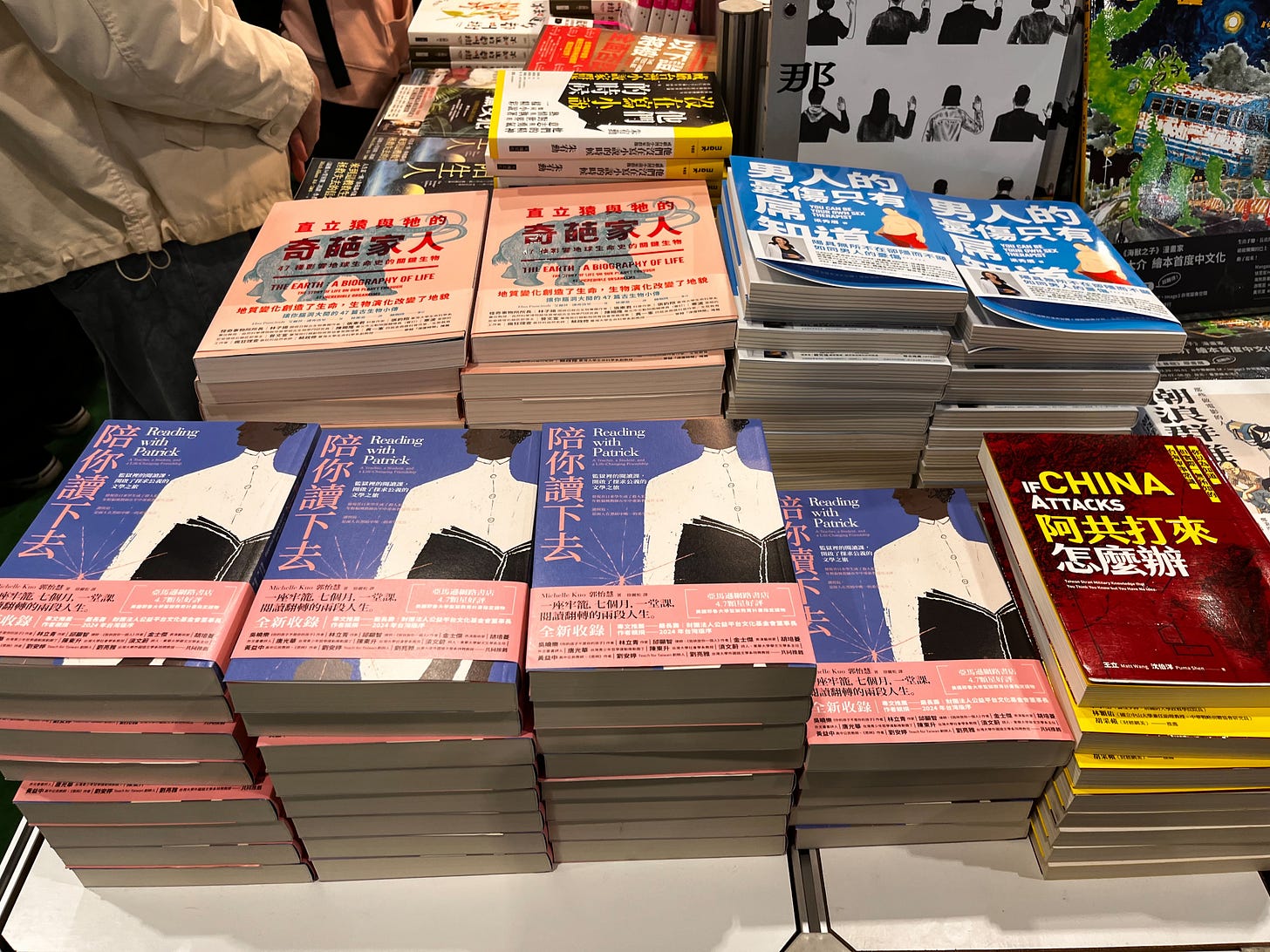

Michelle here. A new Taiwanese edition of my book Reading with Patrick came out this week. Translated by Hsu Lisung and published by Locus Books, it’s called 陪你讀下去.

At its heart, the book is about my experience reading with a former student in a county jail in the Mississippi Delta. As I explain in a new introduction, I’m still preoccupied seven years later by the questions that prompted me to write it: how do we connect across difference? How do we live in a way that coheres with our values? What leads people to commit violence and what repair is possible? How do books help us know ourselves and each other?

On Wednesday morning I spoke at the Taipei International Book Fair with my publisher, Rex How, whose new book Taiwan Unbound Albert and I edited. I’ll share more about him in the future, but he’s essentially the definition of a Renaissance man: the author of many books, but also a lifelong manga fan, fortune teller, former advisor to a presidential administration—and whistleblower who helped spark the Sunflower movement. At his press Locus Books, he championed Annie Ernaux and Olga Tokarczuk almost twenty years before they won their Nobel Prizes. Before he started Locus, he introduced Milan Kundera, Haruki Murakami, and Italo Calvino to Taiwanese readers. Rex came here from Korea fifty years ago—on crutches, due to polio—and never looked back.

Rex and I discussed those crossroads moments in life where you decide who you want to become. We talked about the wonderful Taiwanese readers I’ve met: teachers, activists, lawyers, students, volunteers who write letters to people on death row, librarians who help secure access to books for mothers incarcerated with their children. We talked about the value of books in prison, in schools, in communities. Rex asked how to get kids to keep reading in a digital age, and my answer was to let them choose what they like, the better to discover their own sense of individuality, taste, and intellectual liberty. To avoid being snobby about what they read, and to let them feel free in their own worlds.

But here’s the buried lede: my dad was the event’s interpreter! This was a source of “comical family psychodrama,” as my friend Ian put it. The idea had been floated by Albert a week in advance, and my dad seemed flattered and excited, so I didn’t give it too much more thought. The day before the talk, though, I had begun to veer between aspirational optimism (“Trust him,” Albert said, and I nodded, picturing us bonding on stage) and ruthless truth (“My dad doesn’t know how to listen!” I told Albert. “How is he going to do this?!” (These exchanges were held in hushed voices, because my parents have been living with us for three months and I was paranoid they’d hear me.)

Various kinds of guilt surfaced. Guilt for doubting my dad’s ability, then guilt for criticizing my parents in the book (what a brat!). This morphed into defensive anger, liberally sprinkled with muttering. (“You’re lucky I sanitized those fights we had!” I fantasized about telling them. “If the people really knew!”) And then I started thinking this was all my fault, because my Mandarin still isn’t good enough, after three years in Taiwan, to not need an interpreter. Then back to guilt for being a brat.

The next morning I relaxed and decided: who cares? Do I think my words are so important that I’d fire my own dad? He’s up to the task! I’m lucky he’s alive! He’s a good guy! I’m a jerk!

Then the event happened. We had a lot of fun. Sure, a professional interpreter wouldn’t have omitted large chunks of key points (like how mothers here are incarcerated with their children until age three, which research says is critical to their bonding1), or translated middle-class as middle school (twice), or said, “Sorry, I was daydreaming” when it was his turn to translate, or asked me “What’s the connection?” instead of translating what I’d said. (I was showing a photo of kids kayaking off the eastern coast of Taiwan; more below.) At no point would a professional interpreter have said, “That was too long, I’m not translating that.” But it all worked out. Rex was very natural and freewheeling, taking this trainwreck in stride (sorry for the mixed metaphor), and started to help my dad by translating too.

For me, the moment that made it all worth it was when I described my parents yelling at me to leave the Mississippi Delta and go to law school. This was the part of the book I had dreaded describing, because I didn’t want to make my dad (or my mom, who was in the audience) feel bad. I truncated this part of the story—but, to my surprise, my dad drew it out, throwing in Mandarin phrases that Ian described as “going beyond the meta and touching the dramaturgical.” For instance, my dad said, with great relish, “白養你了!” There’s no exact translation—making it even more authentic as a historical record—but the closest my translator friends and I have come up with is “We raised you for nothing!” The laughter was good to hear, and my dad was clearly rejuvenated by playacting Vigorously Disappointed Circa-2006 Asian Dad.

All of this was sweetly restorative but also had an unfinished quality. As we discussed this period, I omitted the detail that our fights didn’t subside but in fact intensified, especially two years later, when I chose a legal aid job over an offer from a corporate law firm and we stopped speaking altogether. I still have a chip on my shoulder when I meet Asian Americans who do corporate law, picturing their smooth relationships with proud parents (plus they make astoundingly more money than I do). The self-doubt stings too: were my parents right? Why am I getting “low threshold” alerts from the bank?

In the end, though, I like me more than I don’t, and since having a kid of my own I feel for my parents too. How many times have I panicked and yelled at my child for riding her bike down the middle of the street, seemingly indifferent to the risk of getting mowed down by a car?2 In these moments, conflicts I’ve had with my parents—which I know on some level to be trite, First-Worldy, and stereotypically Asian—appear more profound and timeless than I’d given them credit for. For they distill starkly the battle between a child’s pursuit of autonomy and a parent’s desire for control—between one’s pure, determined disregard for danger and the other’s urge to protect. How to mediate these poles? How to guard the inner light that every child radiates, and not let it go out? I have no idea, but I know we have to trust our own instincts. I cry like a tap these days, and am crying as I write this, but I return to the beautiful words of Natalia Ginzburg when I need courage: “What we must remember above all in the education of our children is that their love of life should never weaken.”

As I say in the book’s new introduction, moving to Taiwan has helped me understand my parents, who are instantly recognizable here. Their preferences for my career, their style of parenting, and their expectations of obedience are so typical. It’s been a relief not to have to explain them to anybody; they’re normal, not abnormal, even if they have their own idiosyncrasies. (One student told me that her father said to her, “If you decide to major in sociology, don’t call me Dad.”) Living here, I also get the political context more viscerally: a generation and a half ago, this was a poor country under martial law; to get involved in anything remotely political, especially critical of the state, was like manifesting a death wish. It’s a free democracy now, but old fears are hard to unlearn. Why pursue risk when you can be safe? Many before me made riskier choices with much higher stakes, and experienced the dilemma of wanting to live radically on their own terms while feeling bound by duty and debt to their parents.

Rex asked how one decides to choose the path one takes. I can speak only for myself, but I know that working with people on the margins saves us from self-atomization, the despair that comes from knowing one is living separate from others. I didn’t say this at the event but probably my earliest awakening came from volunteering at a homeless shelter in Boston. On the coldest night that winter, when you would surely die if you slept outside, the doorbell kept ringing. It was 2 A.M. and there was one guy had alcohol on his breath—we were a dry shelter, a rule we obeyed strictly—and I had to decide whether to let him enter. I realized how arbitrary power really is. Why did I, an eighteen year old who had done basically nothing in her life, get to decide what happened to him? Our lives are interconnected, intertwined. The more politically fashionable way to say this is: I’m not free until you’re free. That’s good, too, but I like the spiritually imbued Dostoevskian way—touch one end of the string and the other end moves.

I’ll close with one of the most touching things I heard, from my friends at the Taiwan Innocence Project: one of their clients, Wu Ming-Feng, who’s in a prison in Kaohisung, read my book three times and said it made him feel hopeful about the care teenagers could receive if we all decided to pay attention. Wu was exonerated by TIP but has to serve time for other crimes that occurred as a result of his wrongful conviction. When he gets out, I hope we’ll find ways to collaborate. If you’re in Taiwan, let’s do it together.

*

Here’s the photo that prompted one of the onstage disagreements between my dad and me. (“What’s the connection?”) I was talking about education programs that center connection to place, and this NGO in Taitung, Kids Bookhouse, takes kids kayaking—which reminds me of a very cool nonprofit in the Mississippi Delta that teaches kids how to make canoes and go on river trips.

*

Deep gratitude to everybody at Locus for the new edition, among them Rex, my new editor Odili Lee, Julian, Andrew, Tyler, Trista. Plus my too-cool subagent Gray Tan, and the original gang, my translator Lisung Hsu and my old editor Yahan Chang, who brought the book to Taiwan.

More Scenes from the Fair

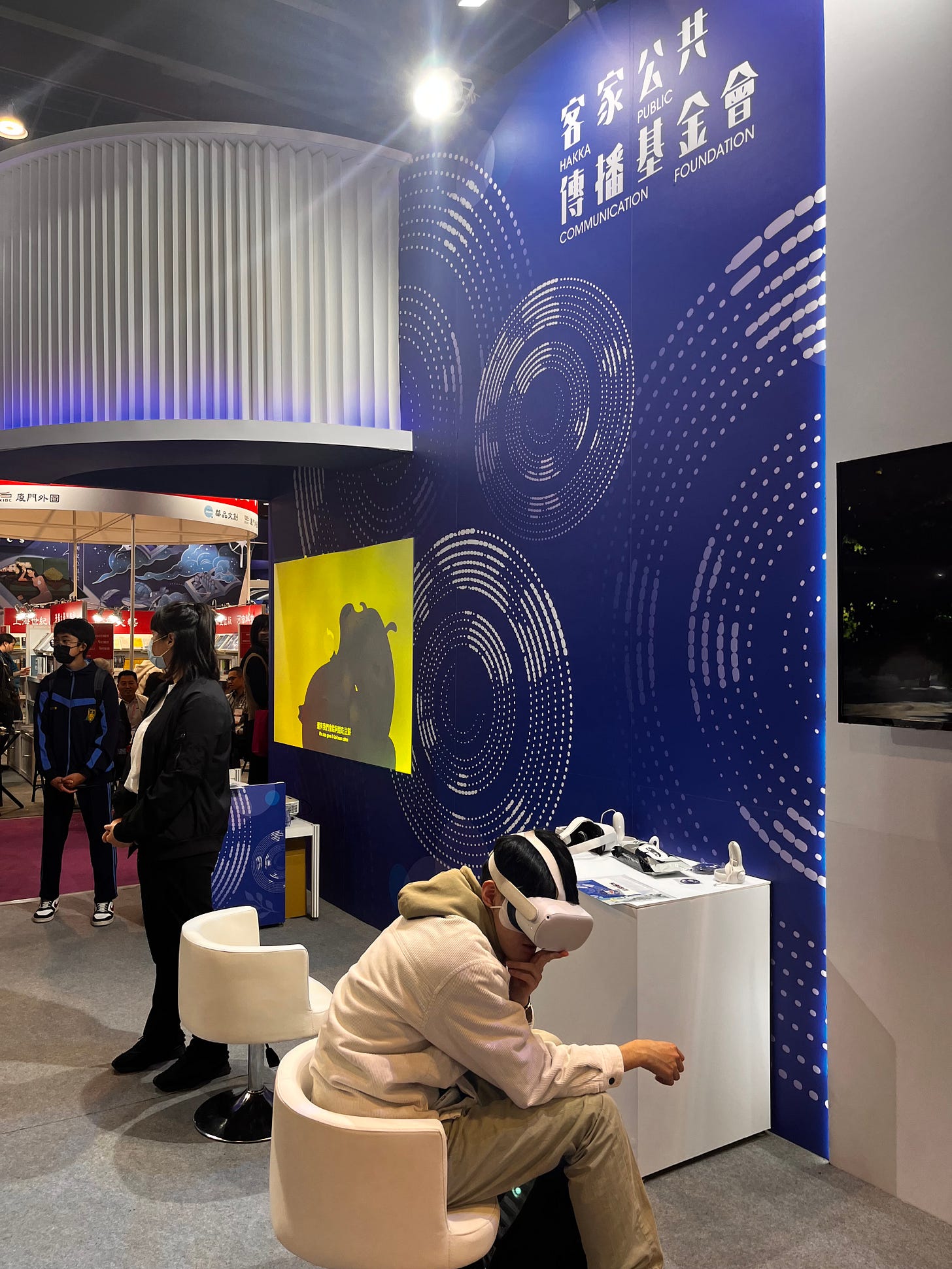

The Taipei International Book Exhibition (TIBE) is perhaps our favorite event in Taiwan. We wrote about the chaotic fun last year (Mandarin version here), and we think this paragraph still captures the spirit of the event:

Taiwan’s most prominent intellectuals, writers, and translators gave talks to standing-room-only audiences—at any given moment, roughly a hundred of these talks were happening. This was not without its FOMO-causing tendencies, but above all it felt like proof of a flourishing Taiwanese democracy, an idiosyncratic and uncensored world of wildly different religious customs, subcultures, and political beliefs all coexisting in sweaty proximity.

The crowds were even more intense this year. Last year, the fear of COVID still lingered. And this year the organizers made a smart move to try to entice more readers: all attendees receive a 100 NTD voucher for any book that they purchase, lowering the cost of attendance to about 2 US dollars while also encouraging people to buy books. Readers from the ages of 16 to 22 could also get in free and accumulate points to get free books and goodies. Apparently this was a huge success—all of our friends in the book industry have remarked at how young the crowds were this year at the book fair.

Here are some photos from the fair:

Links to ordering the translation

Here are some links to order the Chinese translation of Reading with Patrick. I wrote a new introduction, and there’s a new preface by 嚴長壽 (Stanley Yen), a philanthropist helping revitalize rural areas. He’s worked with people such as Lin Hwai-Min through arts and dance programs to create dance performances in Taitung, for instance.

Support Palestine

It’s impossible to write about the metaphorical extinguishment of a child’s inner light without thinking of the actual killing of children in Palestine. I’ve been looking away because I can’t keep looking. Reports of children eating grass, doctors finding sniper bullets in children’s heads. I don’t know what will happen, and I’ve been feeling powerless; if you have any helpful words, I’d like to hear them. Here are some links to support Palestine (and if you have any other places you know are good, tell me). Here’s two: UNRWA and the Palestine Red Crescent Society. Though I could attend only briefly, I wanted to shout out Generation Now Asia for organizing a packed solidarity event earlier this week.

Book Club: EAST GOES WEST

We loved talking to you all about Homegoing! For March, we'll read the “first” Korean-American novel, Younghill Kang's EAST GOES WEST. (It also has a wonderful introduction by Alexander Chee.) This will take place Friday, March 29th at 7 PM EST / Saturday March 30th at 7 AM Taiwan time. For April, we'll read Abraham Verghese's THE COVENANT OF WATER. Email us for the zoom link. All are welcome!

Transitional Justice Events

If you liked our recent post about transitional justice and want to learn more, legal scholar Cheng-yi Huang is hosting a roundtable (in English) on Friday, March 1st at Tsai Lecture Hall 7th Floor, National Taiwan University College of Law at 2 to 4 PM, celebrating the release of his edited volume Constitutionalizing Transitional Justice: How Constitutions and Constitutional Courts Deal with Past Atrocity.

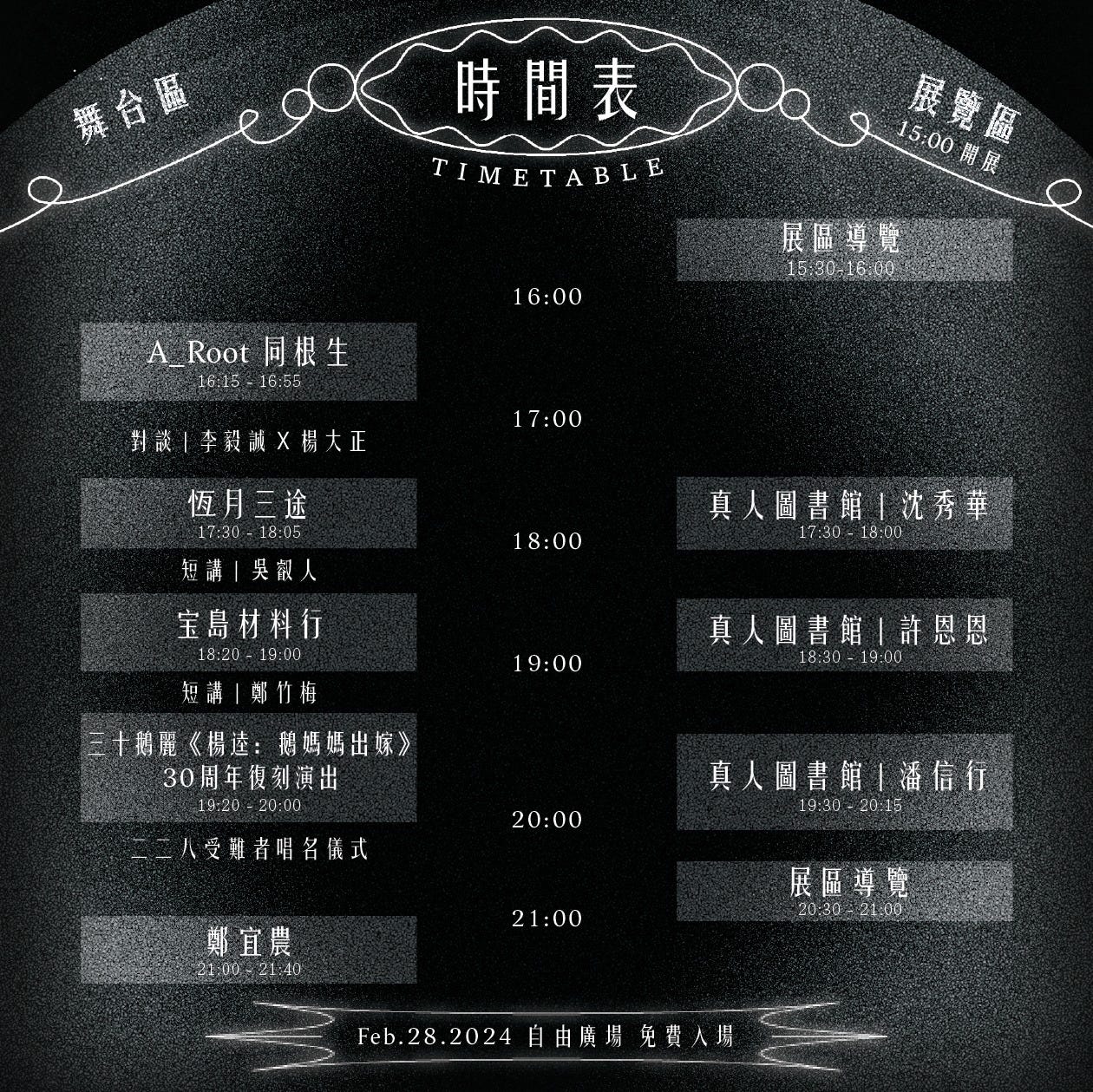

Also check out the Kiong-Seng Music Festival next Wednesday, February 28. This year the festival will be held at Liberty Square, with the opening ceremony at 3:50 PM. The first musical act begins at 16:15.

Alternatives to prison would be ideal but it’s better for kids to be with their mothers than not. In Taiwan, librarians work to provide books to mothers incarcerated with their children.

No Longer Baby P., our four-year-old, can bike now! She basically learned in a day, thanks to all the time she’d spent on the balance bike. She loves her bike so much, a hand-me down from our friend Tricky Taipei.

Michelle, I loved the exchange with your father! And how you related the slight panic of everything that was going on in your head 😆—and then the acceptance of just letting the people we love be who they are ❤️

Thank you, Michelle, for continuing to enlarge my world. What a great post! It was great to see that Reading with Patrick is finding new audiences--and that your dad is daydreaming when he was meant to be listening!

The idea of letting kids "be free in their own worlds" -- I will take that advice to heart!

Also, congratulations on Baby P's newly acquired bike riding skills.