The Island Mother: Guest Essay by Sara Protasi

Plus, our toddler loves this classic Taiwanese book about mung beans; and our upcoming book club on Claire Messud's THIS STRANGE EVENTFUL HISTORY

Today we’re honored to share this lovely and resonant guest essay by Sara Protasi, who describes her time in Taiwan during the pandemic. Born and raised in Italy, Sara is a philosopher, dancer, writer, and mother. She met her husband, who is from Taiwan, when they were studying philosophy in the United States; they both teach at the University of Puget Sound. We had the delight of meeting them within the first months of arriving to Taiwan. Sara’s the author of The Philosophy of Envy (listen to her talk about the book here and here). If you’re new to Sara’s writing, read her provocative essay “Love your frenemy,” which describes how love and envy co-exist, as well as her exploration of the many sides of envy and the myths of love.

Before we forget: Michelle has two upcoming events in Taipei. She’ll be in conversation with Katherine Chang at Bookman Books on Saturday, August 17th at 14:00 to 15:00; registration here. On Sunday, August 4th she’ll be in conversation with Jeffrey Deskovic and Chang Ting-she at the Taiwan Innocence Project’s conference; Deskovic spent 16 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

Thanks dearly for your soulful replies to Michelle’s most recent missive, which explored the ethics and disenchantment of writing Reading with Patrick.

And now, Sara’s piece!

The Island Mother: Reinventing Oneself in Taiwan

A bit more than a year ago, at 5 A.M. on a hot morning in May, I landed in Taipei, my first time back after living there from March 2020 to May 2022—the pandemic years. As I took in the gorgeous view of Taiwan’s northern coast, shining in the light of dawn, I felt a sense of belonging. “You are home!”—a voice said within me.

When did Taiwan become my home? How can it even be my home, when I am clearly, evidently, still a waiguoren (foreigner)? (Just look at me! Just hear me talk!) I have a home country, where I was born: Italy. And I have an adoptive one, the United States. So, what kind of home can Taiwan be?

That question accompanied me during the ride from the airport to my father-in-law’s apartment. As I chatted with the taxi driver, I was surprised to realize that I could understand most of what he was saying. It was only small talk, the usual topics in any encounter between a local and an expat: whether I like the food; if I find the weather too hot; how old my children are. I was happy I could answer, and yet I also felt frustrated that I couldn’t remember simple words.

How can one be home, when one doesn’t know how to say “sky”?

All throughout that long jet-lagged first day, the uncanny feeling of belonging pervaded me. I unpacked my luggage, carefully examining each fragile object meticulously covered in bubble wrap, as is my habit after decades of international moves. I almost broke into tears as I surveyed the familiar rooms that we inhabited during one of the strangest times of our lives—now empty and tidy, the beds covered with plastic, the shelves full of space. Amidst the signs of our prolonged absence, I could see traces of our presence: the bamboo hats and cups the kids got when we visited indigenous villages in Hualien County, in eastern Taiwan; a pack of their “art”, much of which was produced in the first pandemic months in which US classes were online, as we scrambled to find activities to keep them busy; worn-out dresses bought hastily from the traditional market alongside fancier ones from the mall, not nearly as loved.

Why did I feel like crying when looking at these rooms? It should have been a joyous occasion. And yet I was aching.

Perhaps, I speculated, it was because I remembered hard times. In March 2020 when my Taiwanese partner realized that COVID was about to hit the US, he felt a sense of urgency and certainty: “It’s going to be bad,” he said. “We’ll be safer in Taiwan. We need to leave.” He had been monitoring the Taiwanese government’s response to “Wuhan pneumonia”, as they called it then. Taiwan’s Center for Disease Control was already aware of the pandemic at the very end of 2019, and in February 2020 swiftly put into place many countermeasures, including travel restrictions, nationalizing the mask industry, and extensive use of digital technology including contract tracing.

My partner felt confident his home country would protect us better than his adoptive one would. He told me we should leave on Monday, March 8th. We were teaching remotely that week, and then it would be Spring break, after which we would teach remotely for at least one more week. “This will last for longer than people realize, and the kids’ schools will soon close, you’ll see, and they’ll probably be closed until after Spring break. Let’s get out of here.”

I was shocked. How could we leave even before knowing that the elementary schools would close? But then I thought about the news coming from Europe: on that same day the Italian prime minister had announced a nation-wide lockdown. Could the US be next? In a couple of days, anxiety took hold of me and I became increasingly convinced leaving as soon as possible was the right call. “Let’s leave right away,” I said, “if we want to leave, let’s not wait for too long.”

That Wednesday, my partner bought a ticket for Friday night, while I started packing a couple of suitcases in haste, quickly arranging what could be arranged, leaving house and car keys to trusted friends, just as schools around the country indeed went online and people started getting sick. We got to Taipei a few days before the borders were closed, intending to spend just a few weeks. We ended up staying more than two years.

The first few months in which I found myself stranded there were hard. I tried to keep the kids occupied while we taught our college courses online at strange hours. I was worried sick about my Italian relatives and talking to them every day, looking to establish a routine while feeling impermanent and unsettled. The spring ended, and the torrid summer arrived. In August, it became clear it was safer to remain in Taipei, where life went about normally, if wearing masks everywhere. We decided to stay for the school year. Even though I had been studying Mandarin on and off for almost a decade, not much of it had stuck. In my youth, I had been proud of my ability to learn foreign languages, but this language was proving to be insurmountably difficult. I felt lost and disoriented, constantly fatigued by navigating a city where I could barely read a sign or menu. I wept in coffee shops when talking to friends on Zoom. I pitied myself and then shamed myself for it.

We had to plan short frantic trips back home to ensure we didn’t violate the terms of our green cards. The first time I returned to our US house, I almost cried, seeing the traces of our sudden escape to Taiwan—clothes hanging to dry, now stiff; ants feasting on the sugar left in the pantry; books left half-read, splayed out, too heavy to bring with us. I recall telling a friend that I got a glimpse into how refugees must feel when they have to suddenly flee their homes, ridiculous and offensive as that may sound. But on a few hard days, that’s how I felt.

And then something happened. The way in might have been dance. In ballet all steps names are in French and they are the same anywhere in the world. Classes follow a predictable pattern. My partner’s cousin is a former professional dancer and suggested a couple schools. The first I went to was a luminous renovated space in the corner of two major roads, above a bakery where I ended up spending many afternoons sipping coffee and working before class started. The first time I stepped into the studio and set my hand on the barre, I felt reassured and at home. There were some initial minor linguistic struggles: I could not understand the abbreviation for pirouette that people used, and still sometimes confused zuobian (left) and youbian (right). But my anxieties were immediately assuaged by amiable students who complimented my dancing, gently corrected my Mandarin, and translated instructions when needed. I could not understand the jokes of my excellent teacher, but her warmth and kindness and praise enveloped me from the start, making exact comprehension redundant. I made friends. I was proficient in something again.

Then I started taking online classes with a private tutor, and learned enough crucial characters and terms to order a cappuccino or an americano at Louisa, a popular local coffee shop chain, and get food from a xiaochidian (snack bar). I had always enjoyed the food, but now I really loved it, including dishes I previously found a little odd, like douhua (tofu pudding) or ô-á mī-sòaⁿ (oyster vermicelli).

Having the kids back to school also helped, notwithstanding some bumps in the road especially for our oldest, who had to make up one year worth of characters in one summer, and who was embarrassed when I picked her up from school, White English-speaking woman that I am. I joked we were in a witness protection program as she pretended not to know me, walking in front of me and sending silent sideways glances. Now that I write it down, I’m not sure my joke made any sense, but it helped me cope with the hurt I felt.

One school year ended and after a summer back to the US, we went back to Taiwan for our sabbatical leave. This time, I was happy to go back. We had friends, favorite restaurants, parks, and weekend activities. I recognized the vendors at the local market. I spent pleasant afternoons chatting with the owners of the wine bar near our apartment. I always waved at the cook in charge of the Tandoori oven in the fancy Indian restaurant in our block. Whenever you wave at him through the window, he waves back and grins. When I went running in my short shorts, he’d always give me a thumbs up. We’ve never exchanged a word, but he’s as familiar as the other neighborhood inhabitants: the “flower lady”, the fruit sellers, the laoban (boss) of the breakfast places.

And that’s why, I think, I cried that first time back in Taiwan a year ago. Taiwan was past hardships. It was hard-won joys. Taiwan was escaping from a scary reality of disease and death but also encountering novel challenges, conquering smaller fears. Learning a language and moving countries is always a way of reinventing oneself. A new me had emerged in Taiwan and I found its cocoon in our Tianmu apartment.

Now, a year later, I ache to return. My partner and I plan to retire there. He has been wanting to move back for a while now, but it would be too difficult for our children, and as an academic couple it’s really hard to find a job in the same city. And my hometown of Rome is beautiful to visit, but exasperating to live in. My attachment to Italy is natural and completely unchosen, and that’s why I berate Italy all the time. It’s the biological mother I got stuck with from the start, and I tolerate it even as I secretly love it. The United States is the adoptive parent who bailed me out when that irresponsible motherland squandered all its riches and let all the kids, pardon, brains drain out of her. But it’s also a complicated, contradictory country, and I cannot relate to many central features of its identity: its individualism, patriotism, lack of a robust welfare state, and most of all its obsession with guns, more scary now than ever. Taiwan was the caring mom who took me in when disaster struck, the safe harbor during a global pandemic. A country where the government is not distrusted and that takes good care of its citizens. It was an unwitting attachment at first, until I leaned on her. Against all of my initial resistances, I got imprinted on this tiny beautiful insular mother.

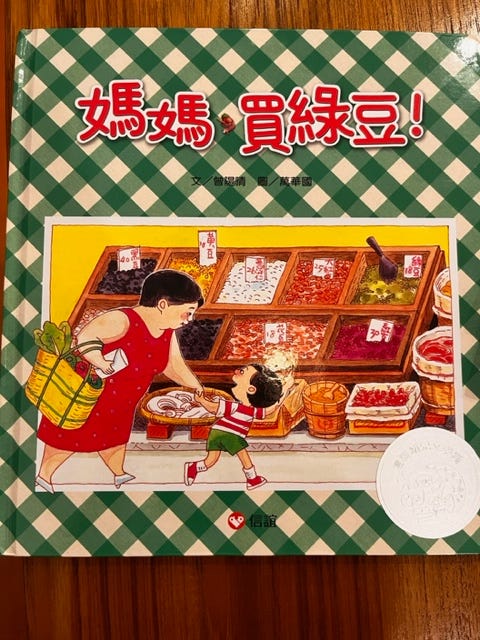

Classic Taiwanese Children’s Book About Mung Beans

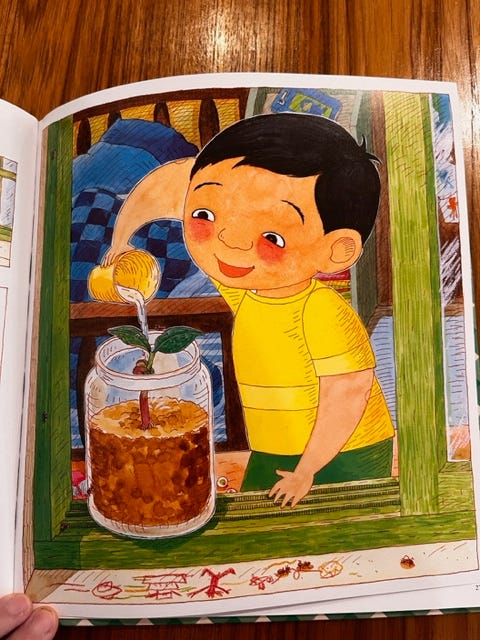

Our four-year-old loves this book about mung beans. She takes it with her everywhere. We’re slightly mystified, because she doesn’t actually like to mung beans. Here’s a glimpse of the book, a gift from our friend Su:

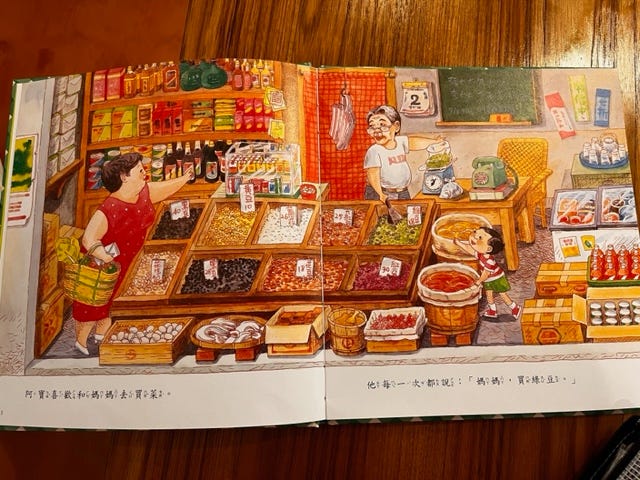

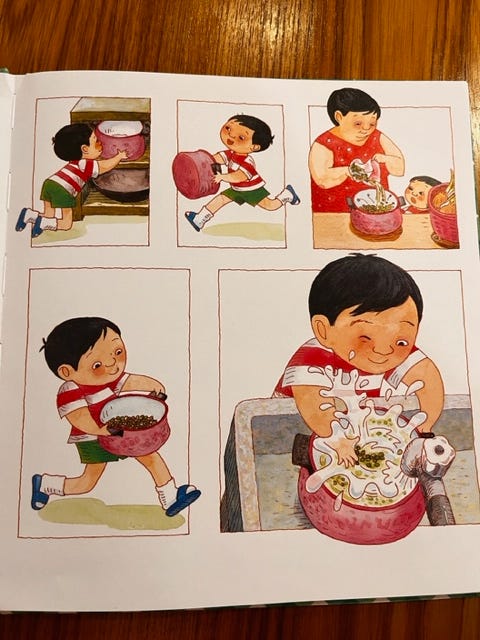

Here she teaches the little boy how to soak the beans:

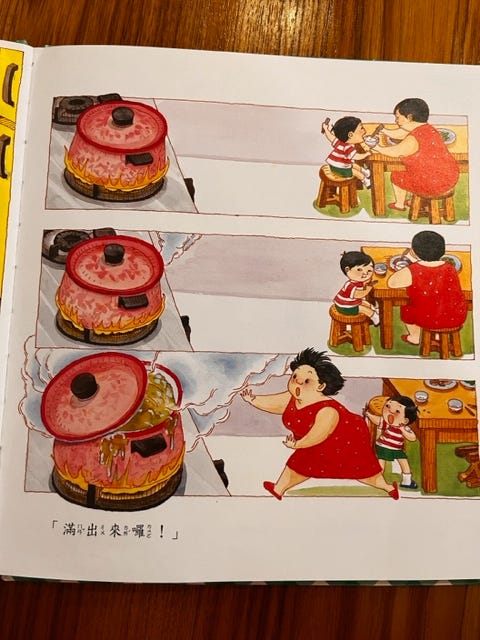

And here’s her favorite page; I think it reminds her of how I’m often forgetting I have something on the stove:

At the end of the book (spoiler alert!) the boy plants his own mung bean:

Book Club: Claire Messud’s This Strange Eventful History

We’re reading Claire Messud's wonderful This Strange Eventful History about a pied-noir French family. Join us on Friday, Aug. 2nd, 7 PM EST / Saturday, Aug 3rd, 7 AM Taiwan time. Then, we’ll read Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse for our gathering on Friday, Aug. 30th / Saturday, Aug. 31 (same time). On Friday, September 27th / Saturday, September 28th we’ll read Andrea Lee’s Red Island House. (If you’re into audiobooks, the reader Bahni Turpin is great.) We loved talking to you about Claire Keegan’s work last month. Reply to this email for the zoom link. Thank you!

That mung bean book looks so cute! What year was it published?

Love this piece! Beautifully written :)