The Troublemaker: Chen Shui-bian Reconsidered, Part 2

Guest essayist Nicholas Haggerty investigates the corruption scandal that engulfed his presidency and makes the case for a pardon.

Dear all,

We hope you’re well! As we expected, Nick Haggerty’s exploration of former Taiwanese president Chen Shui-bian, who was arrested and convicted for charges of corruption, ignited some passionate responses. We’re collecting a batch; please don’t hesitate to add your take. In the meantime, here’s a glimpse: one reader writes that Chen was a traitor whose greed made him betray his party. Another writes, “Although my dad was not very fond of him by the end of his term, he believed that he was treated unfairly by the KMT. My family see the imprisonment of Chen Shui-bian and many of the DPP cabinet members after they left office as political persecution.” And a third shares a recollection that still troubles her: “Each time he was charged of another count, I heard firecrackers. I realized that the joy that people had of locking him up was synonymous to the excitement of Chinese New Year. That’s politics: one man’s suffering can be another man’s moment of triumph.”

This much-anticipated Part 2 investigates the corruption scandal and makes the case for a pardon.

In Chen’s telling, the story of the corruption begins in 2004, in the charged atmosphere of his reelection campaign. As they waved to supporters on a motorcade procession the day before the election, amid the haze and deafening explosions of firecrackers, Chen and running mate Annette Lu were shot by a then-unknown assailant. Both suffered minor injuries. (The prime suspect was later found dead.) That evening, a prominent talk show host accused them of staging the assassination attempt to elicit sympathy votes. Chen and Lu won by less than a percentage point, and the KMT candidate didn’t concede, calling the election unfair. Mass protests calling for a recount were held outside the presidential palace, but Chen’s fear was a “soft coup” of coordinated military brass resignations. (He avoided this, he claims, because he saw through the plot and played rival generals against one another.)

Opposition to Chen would really begin to cohere in the spring of 2006, as the recall campaign played out over his permanent adjournment of the national unification council, when stories began to appear in the media alleging that the first family had traded on their political power for cash. Soon after came more damning accusations, in the “state affairs expenses” case, of improper applications for reimbursement of personal expenses. The recall vote in the legislature failed in June, but by autumn Chen faced hundreds of thousands of red-shirted protesters in Taipei, commanded by Shih Ming-teh, an old comrade from the struggle against KMT authoritarianism with a great deal of moral authority.

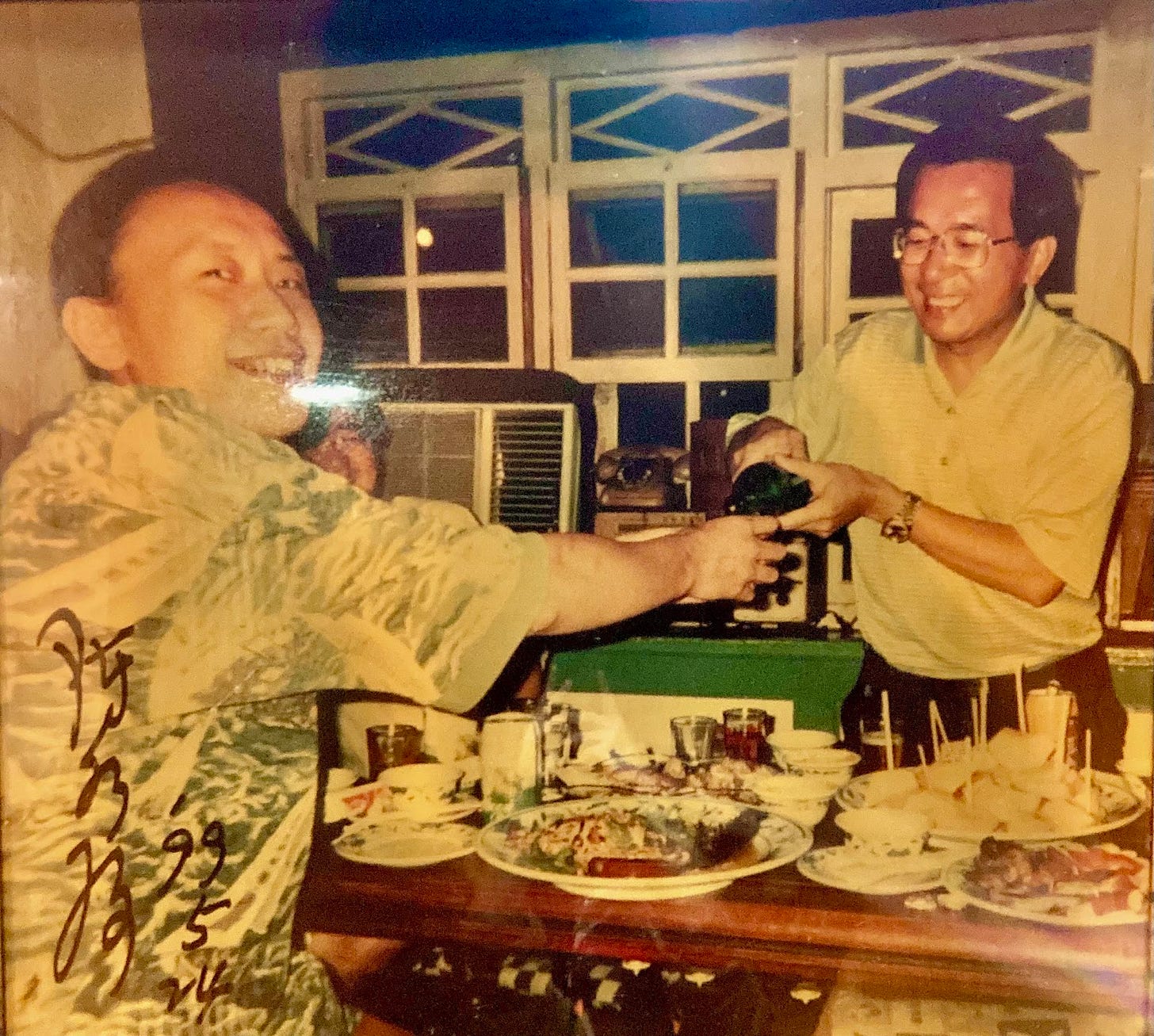

After the uproar in the media and on the streets, indictments of Chen’s wife and top aides soon followed. Chen denied misuse of the accounts, but delegated authority to his premier, as though acknowledging his diminished stature. The brunt of the scandals may have appeared over to Chen in the months before completing his term in May 2008. “Relaxed and cheerful” is how the de facto U.S. ambassador described him at a private dinner during his final Lunar New Year’s in office, as he mused about his post-presidency travel plans.

In August 2008, though, a KMT legislator disclosed a letter from Swiss to Taiwanese authorities requesting assistance in investigating around $30 million wired to a Swiss bank account by Chen’s family. By November of that year, while the world was distracted by the financial crisis, Obama’s rise, and China’s post-Olympic glow, Chen was perp-walked out of the prosecutor’s office into a pre-indictment detention. In his last major turn in the spotlight, he raised his handcuffs above his head and proclaimed his detention to be political persecution.

The word of legal scholar Jerome Cohen, normally an authoritative voice on politics and law in the Chinese-speaking world, is especially powerful in determining the international consensus on whether Chen received a fair trial. In the 1980s, he made representations to his former student, Ma Ying-jeou, then the president’s English translator, on behalf of another former student serving time as a political prisoner, Chen’s future vice president Annette Lu. No similar intervention arrived this time. “This was corruption. This was money corrupting the regime,” Cohen has said. But Cohen has also consistently raised the legal ethics violations committed by the prosecution, like a skit performed by the prosecutors satirizing Chen’s handcuff gesture, and has called “bizarre” the Taipei District Court decision to have Chen’s case transferred away from a judge who had originally released him from detention. Wang Jaw-perng, a leading expert on criminal procedure in Taiwan, has cited Chen’s long pre-trial detention, during which his conversations with his attorney were recorded and used as evidence in court, to conclude that his 2009 trial was not fair, though like Cohen, he believes that Chen is guilty of that which he was charged.

The state affairs expenses conviction, which led to Chen’s life sentence, would be mostly overturned on first appeal. The not guilty decision would be vacated on a second appeal. A final decision by the Taiwan High Court has lingered, undecided, for about a decade. The boundaries of public and private expenses remain the subject of a live debate in the legislature, as thousands of government officials could be implicated, most of all Chen’s successors Ma and Tsai. Also relevant is the lack of precedent, Chen being only the second popularly elected president in a system whose previous occupants were protected by a compliant judicial system. The first, Lee Teng-hui, who was mourned across Taiwan as the father of the nation’s democracy, was a notorious merchant of “black gold,” under-the-table cash of typically criminal provenance, for political use. The class aspect of Lee, a child of the Japanese-era elite, also can’t be gainsaid; he appears as a national figurehead more befitting the prosperous in today’s Taiwan than someone of Chen’s earthy manners ever could.

Investigations into the state affairs expenses case eventually exposed an influence-peddling operation, nominally run by the first lady. Chen was found guilty of acting on behalf of three parties that made off-the-books cash payments to him or his wife: a cement corporation seeking to sell off land, an executive pursuing an appointment to the chair of Taipei 101’s holding company, and a bank expecting non-interference in a merger. Millions from these deals—and probably similar ones that weren’t provable in court—were wired to secretive overseas accounts and used to purchase a suburban home in Virginia for $550,000 and a Manhattan condo for $1.6 million. The convictions amounted to millions in fines and eventually a reduced sentence of twenty years, which Chen served until the compassionate release was handed down.

It may be useful, for this act in the tragedy, to recall Lula. Perry Anderson, in his essays on Brazil’s recent political history, describes convincingly how Lula’s scandals didn’t cast doubt on the sincerity of his commitment to social uplift for poor Brazilians. His mensalão bribes to congress could even be viewed as bold, an acceptance of the necessity of wading into the mire to return with minimum-wage increases and programs like the immensely popular Bolsa Família cash subsidy for families. In Operation Car Wash, the worst Lula was accused of was accepting the offer of a $600,000 apartment he would never actually own; he was also the victim of serious judicial misconduct. Considering the generalized corruption of Brazilian politics, Lula’s record of forging a coalition in support of social democracy, and Bolsonaro’s threat to the Amazon and to Brazilian society at large, the allegations are of no moment to his supporters around the world.

Chen’s cash distributions resemble Lula’s in that they were made to support his political aims and not, he maintains, for private benefit. “Who hasn’t taken money from my Dad?” his daughter once asked reporters, rhetorically, at the scandal’s peak. Prompted with this quote in a recent interview, Chen said he was a prolific benefactor to political allies: “Who can say that they haven’t taken A-Bian’s money?” His party and affiliates like the Taiwan Solidarity Union needed money for running campaigns; the KMT that Chen was up against still had substantial party assets and overwhelming support from big business. Chen was the one most willing and able to procure the resources needed to win. The DPP, Chen revealed to American diplomats, lacked funds to support candidates adequately.

The two U.S. properties aside, it’s difficult to conclude that he was motivated by greed. Still, his critics maintain, neither was the operation motivated by selflessness, as he was able to use his control over the flow of money to consolidate his position within his party. The difference with Lula is that all Chen’s deal-making did nothing to further a social democratic program. In the leadup to the 2000 election, he spoke of a “Third Way” between left and right, going straight to the source by befriending Tony Blair’s house intellectual Anthony Giddens. In office, he saw to completion the privatization of state assets (the process had begun in the 1980s) in sectors like telecommunications and financial services. He kept the minimum wage flat until his last year in power, an executive branch power over which he had control. The centerpiece of Taiwan’s social welfare system, national health insurance, was bequeathed by his predecessor Lee. He made tax cuts for the wealthy and offered personnel appointments to business interests and political allies. While these acts won him friends where they seemed to have counted most, and transferred economic power away from the KMT stronghold in the state bureaucracy, one can hardly consider them progressive achievements. In short, Chen failed to develop a social and economic vision to accompany his nation-building.

Yet even if he did have the ambition to enact a widespread transformation of Taiwanese society, could he have done so? I doubt it. What comes across repeatedly in his memoir is Chen’s profound vulnerability throughout his time in office. Having been elected with only 39 percent of the vote, just over a decade removed from martial law, his fears of a military coup from KMT loyalist generals do not appear to me as groundless paranoia. The KMT opposition sought to undermine the legitimacy of the government by engaging in party-level talks with the Chinese Communist Party. The United States, in pursuit of closer ties with China, also undermined Chen’s standing internationally. Despite these constraints, he was able to enact lasting domestic reforms, from the curriculum changes, to appointing the first Taiwan-born Minister of National Defense as part of his efforts to transform the military from an arm of the KMT into a force fully subordinate to civilian authority.

Unlike his contemporaries at the pope’s funeral, unlike the Bushes and Blairs of the world, we might imagine that if Taiwan had the powerful left and labor movements that nurtured Lula, they would have at least had Chen’s ear, if not in him, a once in a generation leader. Perhaps he wouldn’t have relied on the shady deals to prop himself up. After all, he knows poverty, has a magnetic, personal charm, and sustains a sense of righteous anger at the injustices of the world—the Lula formula to a T. And his crimes, such as they are, outdone by counterparts abroad with little or no legal consequence, made much less trouble than the senseless, murderous destruction of Iraq overseen by the man rumored to have called Chen a “troublemaker.”

The precedent for a pardon most familiar to Americans is that of Richard Nixon. A popular president of an established democracy, Nixon faced nothing like Chen’s challenges in lifting a weak opposition movement into power against a party with access to vast resources, eliciting the disapproval of regional and world powers in the process, making Chen’s case, in my view, more compelling than Nixon’s. Rather, Chen’s more direct analogue is his contemporary Roh Moo-hyun, president of South Korea. Roh too was a lawyer raised in rural poverty, a principled opponent of his country’s dictatorship, though arguably more left-oriented. If the content of their nationalist visions differed—Chen working toward a distinct Taiwanese community, Roh toward Korean unification—the geopolitical form their efforts took was the same: both were up against Bush-era U.S. policy in East Asia, and both were at the helm of states defined by what Bruce Cumings calls “lateral weakness” to act independently of the United States. Cumings’s characterization of South Korea in the late ’80s also applies to Taiwan today: it is a country “hyper-sensitive” to any changes in its relations with the U.S. Might their common lot, their taking on the role of scapegoat, be traced to their displeasing the imperial overlord without actually delivering on their dreams and promises of national autonomy?

Roh finished his term deeply unpopular, and died by suicide in 2009 after prosecutors started looking into his financial affairs. It’s practically a rite of passage for South Korean presidents to be imprisoned for corruption, though there are signs this is changing: the Korean Ministry of Justice recently pardoned former president Park Geun-hye, someone who can’t claim even a fraction of the substance or principles of a Roh, or Chen. Park’s poor health was relevant to the decision, and it was granted to “open a new era of consolidation and harmony.” Indeed, there may be a growing recognition in Korea that lengthy jail sentences for ex-presidents do little to promote virtuous, uncorrupt governance.

Critics might argue that a pardon thwarts the workings of the justice system. But a pardon can be particularly meaningful in the context of Taiwan’s young democracy. When Chen was elected, campaign finance laws and the political party system itself were not yet institutionalized. As David Tait writes, pardons have a broader political significance than the mere act of forgiveness. Pardons recognize “the violent basis of the social contract and remind us of the fragility of the social order. By depriving the subject of liberty, property or even life, the state shows the violence implicit in its exercise of power. By providing forgiveness, the state shows both its strength and its weakness: its authority extends to moderating or preventing violence, but its own survival depends in part on the selective withholding of force rather than its routine deployment.” A pardon elevates and expresses the value of forgiveness.

As a public act of mercy, a pardon would be best instituted as part of a rolling jubilee of restorative justice for many cases that deserve reconsideration. Ma Ying-jeou has been in legal peril since leaving office—he should be included too. Those languishing on death row, the thousands of prisoners doing hard time in Taiwan’s punitive justice system, all should be considered individually with careful attention to the variety and collision of circumstances that led to their incarceration as well as evidence that they no longer pose a danger to public safety and have been rehabilitated. In Chen’s case, he is a man who led an effort to reconstitute the social order and create a peaceful, democratic society in Taiwan. He didn’t always succeed and sometimes stumbled. But deepening a culture of forgiveness continues the project of democracy, and Chen deserves an act of grace.

Book Club and Other Updates

Michelle here. Our Brothers Karamazov virtual book club continues this Friday, February 25th at 7 PM EST. All are welcome! The zoom link is the same. For March we will read Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies. Please put Friday, March 25th at 7 PM EST (8 AM Taiwan time) in your calendar.

This week we published in Mandarin the translation of Bonny Ling’s moving essay on migrant workers. (Read the original English version here.) Last week we published the essay about the death penalty by Lihan Luo (羅禮涵) in Mandarin. And as we referenced above, here is Part 1 of Nick’s essay.

And to close out this letter, here’s a plate of tea tree noodles from Maokong, a village famous for its tea; it sits atop a mountain on the outskirts of Taipei. Simple and delicious, they’re nothing like other noodles I’ve had. I’ve been dreaming about these noodles ever since I discovered them in 2019, when Albert and I took 18 college students on a trip to Taiwan. I took one bite and thought I’d went to heaven. Then, out of some notion of teacherly politeness, I let the other students at the table finish the plate; I have regretted that decision ever since.

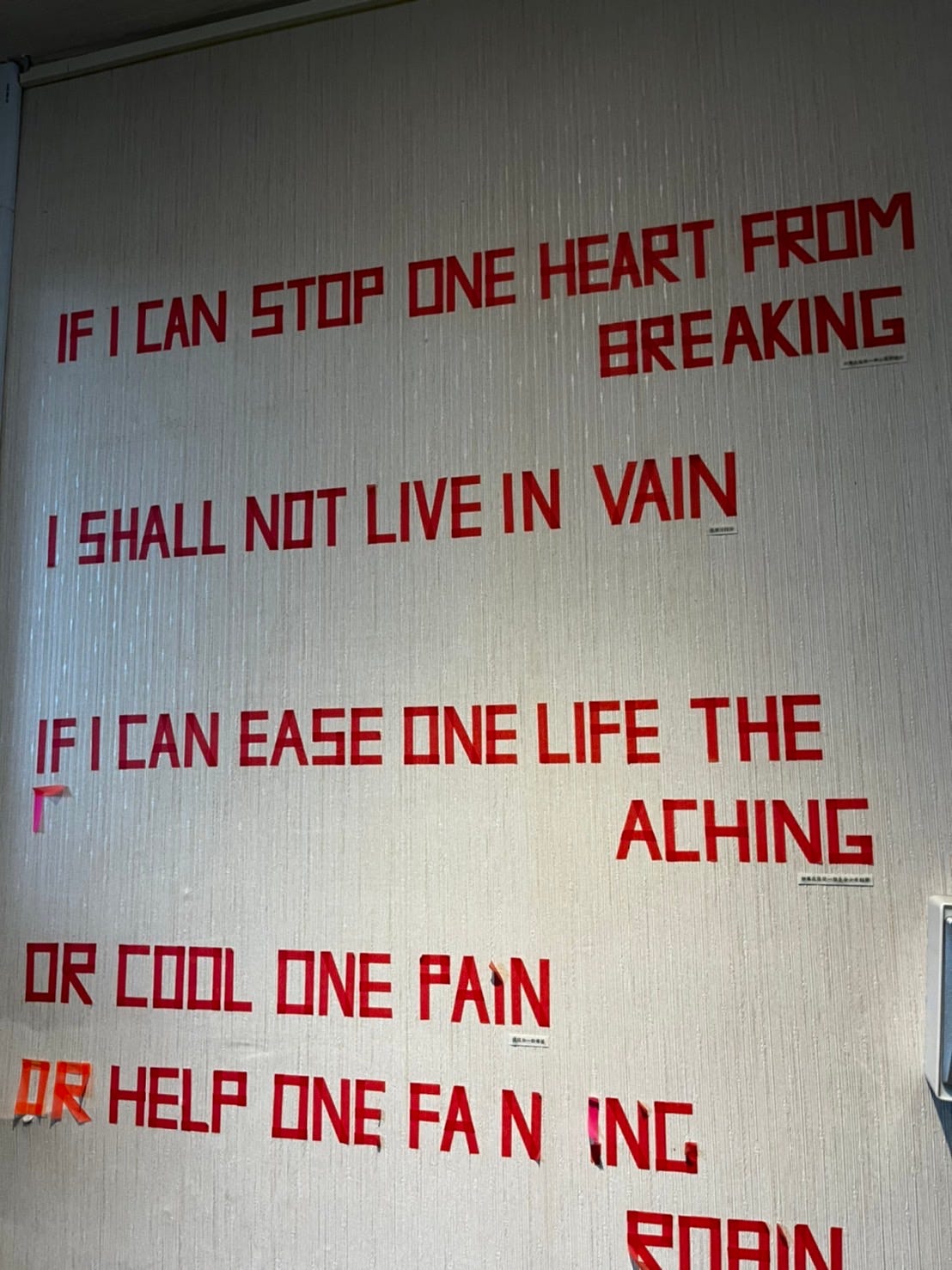

I also loved spotting this stenciled Emily Dickinson poem on the walls of the Taiwan Innocence Project, which I had the pleasure of visiting this week. So far the project has exonerated ten people, including those on death row. I am excited about getting involved with their work.